People of color historically disadvantaged by the nation’s marijuana laws are largely missing out on burgeoning cannabis opportunities and wealth now that legalization spreads across the states—and minority entrepreneurs are pushing for change.

“I was the only Black woman for a long time in a lot of rooms—sometimes, still am,” said Iyana Edouard, a 27-year-old cannabis marketing specialist and content creator in California. For five years, she ran Kush & Cute, a small business that sold hemp skin care products.

When Edouard launched her company, it was one of the few brands of its kind owned by a Black woman, but as the industry grew in popularity, the influx of regulations and corporate competition made it “a lot harder for the small people to stay in the game,” she said in a telephone interview. In May, Edouard put a pause on Kush & Cute.

Minorities, including women, may find the cannabis sector of today cultivating more diversity, Edouard said, but “it is easier for White, wealthy women to get in the space because they have the resources.”

Because weed is outlawed federally, bank loans and tax breaks aren’t an option for people of color lacking ample financial backing. Meanwhile, venture capitalists and businesses with angel investors build their own cannabis empires.

Photo: Courtesy of Iyana Edouard

Iyana Edouard founded Kush & Cute, a small hemp skin care products business.

While a handful of Black celebrities, including rappers Snoop Dogg and Jay-Z, have successfully broken into the industry, they’re outliers in a White-dominated sector. About 80% of marijuana business owners and founders identify as White, according to a 2017 survey by Marijuana Business Daily. Only 5.7% of these entrepreneurs are Hispanic or Latino, and 4.3% are Black.

“It’s not easy,” said 25-year-old C.J. Wallace, who launched Think BIG, a Black-owned company focused on cannabis legalization and other social justice issues. It previously sold limited-edition cannabis products in 2019.

As the son of the late rapper Biggie Smalls, his family legacy gives him a unique platform, but financing his business through investors and other sources is still a challenge.

“It hasn’t gone as well as people would think,” Los Angeles-based Wallace said, adding that he’s seen improvements for his company over the past year.

Federal legalization could resolve a lot of the challenges by lifting heavy financial restrictions. But despite Democratic support, legalization is still a far cry from reality under the Biden administration.

So equity advocates are pushing for smaller wins through other legislative vehicles, such as a House-passed bill (H.R. 1996) introduced by Rep. Ed Perlmutter (D-Colo.) that would offer protections to financial institutions that choose to serve cannabis businesses.

The marijuana industry “really is about money and power,” Edouard said. “It’s unfortunate, but I’m hoping it’s going to change.”

Photo: Courtesy of Think BIG

C.J. Wallace founded Think BIG, a Black-owned company focused on cannabis legalization and social justice issues.

Racial Disparities

The staggering racial disparity in the cannabis sector reflects a similar trend in the overarching agriculture industry, where more than 96% of the nation’s roughly 2 million farms are run by White producers and Black farmers claim about 35,000 farms, according to the latest Agriculture Department census.

Farm Groups See Racism in Agriculture and Promise to Seek Change

Cannabis advocates hope to spark discourse around racial disparities in their sector, pointing to the nation’s controversial history of marijuana prohibition—and the industry’s current legal complexities—that disproportionately hurt marginalized communities.

President Richard Nixon launched his war on drugs in 1971, moving to classify marijuana as a Schedule I drug. His domestic policy adviser, John Ehrlichman, told journalist Dan Baum in 1994: “By getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and Blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities.”

People of color ultimately paid the price, with Black Americans being 3.6 times more likely than Whites to get arrested for marijuana charges, the American Civil Liberties Union found in 2020.

Cannabis business owners need to “recognize that the market they’re in was built entirely on the backs of people of color being arrested,” said Morgan Fox, spokesman for the National Cannabis Industry Association.

Federal Solutions

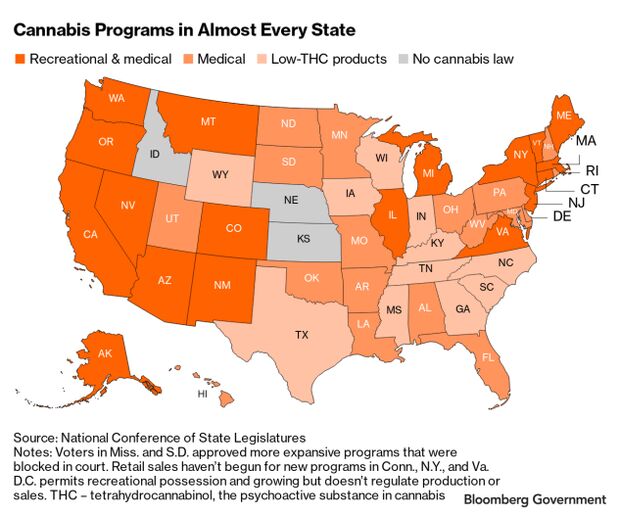

The federal government still considers cannabis illegal, although the majority of U.S. states—36—permit medical cannabis use, the National Conference of State Legislatures reported as of May. Adults can use recreational marijuana in 18 states and Washington, D.C., according to the group’s count in June.

The current federal policy means traditional lending, along with Small Business Administration loans and grants, are “off the table” for cannabis entrepreneurs, Fox said. Those are benefits that marginalized communities “traditionally have needed in order to be able to get into difficult, heavily-restricted industries.”

He highlighted Perlmutter’s bipartisan bill, cosponsored by more than 150 House members, as one legislative solution to promote better access to capital. The measure would give cannabis businesses an opportunity to use the banking system in states with some form of legalized marijuana.

Fox’s group is pushing to remove marijuana from the Controlled Substances Act, which sets U.S. drug policy. Descheduling cannabis would mean eliminating federal punishment around its use, which could allow it to be treated instead like caffeine or alcohol, according to the Reason Foundation, a think tank.

Fox also advocates for restorative justice provisions, such as expunging criminal records. As the legal cannabis industry rakes in billions of dollars, many Americans are still held back by their criminal records, with some marijuana charges considered felonies.

Kaliko Castille, president of the Minority Cannabis Business Association’s board of directors, pushed for state incentives to expunge records. He’s also advocating for more people of color to help write related state and federal policies.

He still sees a future where the marijuana industry transforms into a level playing field for all entrepreneurs, although the clock is ticking as fewer opportunities remain to equitably shape cannabis laws in states entering the market.

“I don’t think that it’s a foregone conclusion that we will not be able to show a new way that an industry can be set up,” Castille said. But the window for change is “rapidly closing.”

More: Click here for a video on how marijuana is both legal and illegal in the U.S.

To contact the reporter on this story: Megan U. Boyanton in Washington at mboyanton@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Gregory Henderson at ghenderson@bloombergindustry.com; Fawn Johnson at fjohnson@bloombergindustry.com

Be the first to comment