When Alejandro Cortez stepped into a Denver marijuana dispensary for the first time this year, he expected to spend at least $150. A Hawaii resident, Cortez eagerly perused the vividly colored buds and glossy edibles he’d read about online, a childlike grin on his face. Then he got to the cash register.

“The taxes made everything cost about $40 higher than the price tags showed. I didn’t know they were so high,” he says.

The overall tab was still cheaper than what Cortez was used to paying on the islands, where recreational marijuana sales aren’t legal yet, and the fun of buying legal weed for the first time more than justified the cost. Still, he left the dispensary looking at his receipt and the 26.41 percent in sales taxes he’d just paid, scratching his head.

“I know stores don’t really do this, but it’d be easier if they just included the taxes on the price we see, because I didn’t see that coming,” the tourist says. “I’m glad I had a few extra twenties on me.”

Marijuana purchases carry a high sales tax compared to the taxes on other retail industries — even so-called “sin taxes” on tobacco, alcohol and other items — in virtually every state where recreational cannabis is legal. Colorado currently has the third-highest marijuana tax rates in the country, after California and Washington.

The tax rates surprise rookie customers and still frustrate regulars, according to Shannon Fender, public affairs director for dispensary chain Native Roots. “Anecdotally, what we hear from our employees is that people are still shocked at the price of what they thought they were buying versus what the actual tally is,” she says. “We’re about at the maximum of what consumers would tolerate.”

And it could be worse.

Colorado currently imposes a 15 percent special state sales tax on recreational marijuana sales, as well as a 15 percent excise tax on wholesale transactions; that’s a bump from the 10 percent sales tax called for in Amendment 64, which Colorado voters approved in November 2012, legalizing the sale of recreational marijuana in the state. (When the Colorado Legislature increased the tax rate in 2017, it eliminated the state’s 2.9 percent standard sales tax from pot transactions.) Local governments add their own marijuana sales and industry taxes on top of the state taxes, giving most recreational pot purchases a tax rate in the mid- to high 20s.

Colorado’s relationship with marijuana didn’t start out with so many tax implications. Dispensaries weren’t on voters’ minds when they legalized medical marijuana in 2000, and medical marijuana transactions only carried the state’s standard sales tax when they began popping up eight years later, after the Barack Obama administration loosened federal enforcement on states with legal pot. Medical marijuana purchases still only carry the standard sales tax rate of 2.9 percent at the state level, and don’t require special sales or excise taxes, as their recreational counterparts do.

Between 2014, when rec sales actually began, and September 2021, the State of Colorado has raised over $1.9 billion in marijuana tax revenue, according to the Marijuana Enforcement Division.

As more states legalize commercial pot and Congress begins talking about federal legalization, local marijuana business owners worry that any hikes to the state’s tax structure could hurt Colorado’s competitive lead in commercial cannabis, and perhaps even push consumers back to the black market.

With Colorado marijuana sales continuing strong, many causes and campaigns still view pot taxes as a fertile area for funding. But insiders worry that Colorado’s cannabis industry could go up in smoke if taxes go much higher.

Former state senator Mike Johnston was a vocal proponent of Proposition 119.

Kenzie Bruce

In the Beginning

Tax revenue to benefit education was a big factor in getting non-users to support recreational legalization in 2012 — and despite Colorado’s reputation as a stoner state, the vast majority of its residents aren’t users. According to a 2021 report from the state Division of Criminal Justice, over 80 percent of Colorado adults report no marijuana use within the past month.

So when Proposition 119 — a statewide ballot question asking for an increase in marijuana sales taxes to help fund a new out-of-school education program — was introduced earlier this year, another hike seemed to be on the horizon. Over $2.5 million was raised in support of the proposition, compared to just $66,346 by groups opposing it.

But in an electoral upset, on November 2 voters decided against raising state pot taxes. Initially viewed as a favorite to win, Prop 119 was ultimately rejected by more than an 8 percent margin of the voters.

And it wasn’t the only defeat for new marijuana taxes at the ballot box. But while the marijuana industry is enjoying the victories, the defeats of the proposals might say more about the initiatives themselves than they do a desire to keep costs lower at the pot shop.

Proposition 119, the proposed State Learning Enrichment and Academic Progress Initiative (LEAP), would have funded annual stipends to cover such out-of-school learning services as after-school programs, individual tutoring and specialized after-school classes. According to proponents, the stipends were going to be prioritized for lower- and middle-income families, who can get lost in the gap of out-of-school educational achievement. A 5 percent recreational marijuana sales tax increase combined with the repurposing of a portion of investment revenue derived from leases, rents and royalties paid for state-owned lands would have funded the program.

Organizations like Mile High Early Learning, Servicios de la Raza and Gary Community Ventures, a nonprofit that spent nearly $1 million on the proposal’s campaign, pushed Prop 119 hard as the election neared, gaining endorsements from Governor Jared Polis as well as former governors Bill Ritter and Bill Owens and former Denver mayors Wellington Webb and Federico Peña.

Gary Community Ventures CEO Mike Johnston, an educator, former state senator and Democratic gubernatorial candidate, thought that a proposal calling for additional marijuana taxes to further educational initiatives would be a winner during an off-year election with lower turnout.

“This is an issue the marijuana industry should care about — kids and at-risk kids having positive places to go out of school,” Johnston says. “Summer break is a time when marijuana use can make an impact on kids, so I think it’s a compelling use of marijuana tax money.”

But while educational funding was a major selling point for recreational marijuana’s initial legalization, a common complaint among Coloradans since 2014 has been a lack of transparency in how that money directly impacts schools.

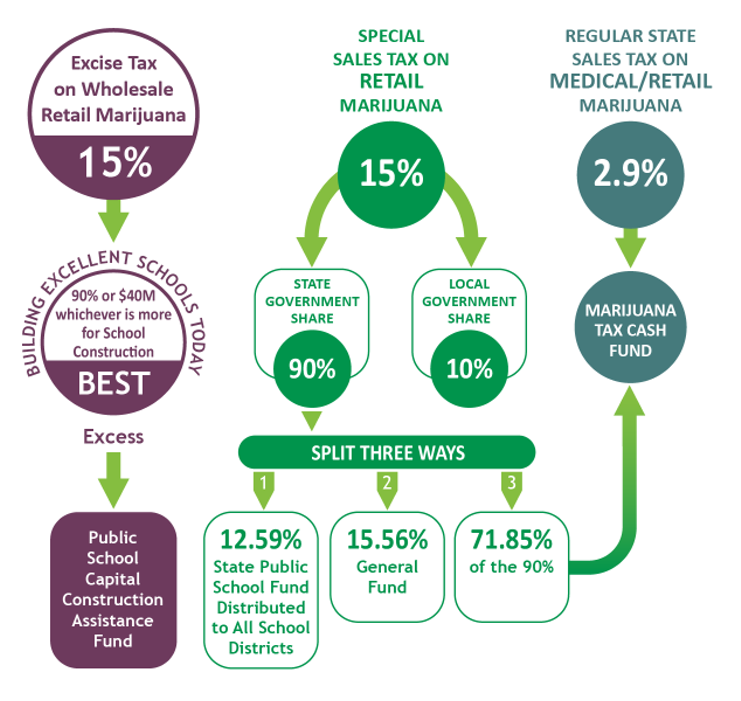

Public education in Colorado receives marijuana tax revenue through the state’s Building Excellent Schools Today (BEST) fund — a matching grant program — and the Marijuana Tax Cash Fund. Local governments can distribute their own marijuana tax revenue to schools, as well. The BEST fund annually receives either $40 million or 90 percent of the state’s 15 percent wholesale and excise tax revenue on recreational pot sales, whichever is greater.

A program for public schools to rebuild, repair or replace primary educational facilities, the BEST fund has received approximately $329.7 million from marijuana tax revenue since recreational sales began in 2014, according to the Colorado Department of Education. However, attaining a BEST grant is “competitive” and has to be matched by local district funding, the CDE adds.

The state’s Marijuana Tax Cash Fund, built on the 15 percent sales tax, was created by the Colorado Legislature in 2014 to support health-care, substance-abuse, law-enforcement and marijuana-impact research, as well as public school programs, with marijuana tax revenue. Between 2014 and 2020, the Marijuana Tax Cash Fund contributed over $193 million to literacy grants, anti-bullying initiatives, dropout prevention and the hiring of public-health professionals in public schools, according to the CDE.

Revenue allocated to the Colorado State Public School Fund — a general education fund built on 12.59 percent of the state’s nine-tenths share of the special sales tax on recreational pot and available to all school districts — in 2021 has not yet been reported; from 2017 to 2020, the average annual marijuana tax revenue contribution to the fund was $25 million.

The remaining tax revenue from the state’s special sales tax on recreational marijuana goes to the General Fund and a local government shareback program for cities and counties with marijuana businesses, which receives 10 percent. Revenue from Colorado’s 2.9 percent standard sales tax on pot sales also goes toward the Marijuana Tax Cash Fund.

Marijuana tax revenue goes in a lot of directions, but this Colorado Department of Education graph breaks it all down.

Colorado Department of Education

Although Colorado’s public schools have received over a half-billion dollars in funding from marijuana sales since 2014, that number pales in comparison to the state’s overall funding for public education, which totaled around $6.3 billion for fiscal year 2020-2021 alone.

Mason Tvert, a marijuana policy consultant who’s worked on marijuana legalization campaigns in Colorado and across the country, called opposing Prop 119 “a tough position to be in politically,” adding that educating the public on marijuana tax revenue allocation has been a constant endeavor since recreational sales began in 2014.

“You’ve got folks arguing this tax was needed to benefit children and education, but also a large lineup of political leaders getting behind it,” he says. “I think there’s been a lot of publicity around the amount of revenue that has been generated, but it’s tough.”

The LEAP program faced increased criticism from public educators, who questioned how accessible LEAP stipends would be for rural and low-income students and said they preferred that public schools receive the money directly. Providers of free out-of-school programming opposed the proposed funding allocation as well, as only for-cost services would have been eligible for LEAP.

The proposed board that would have overseen how LEAP funds were spent also came under fire. Under 119’s language, the board would have been appointed by the governor and replaced every three years by the governor, but only from a list of candidates created by current LEAP boardmembers — and without any legislative oversight.

Former state representative Jonathan Singer was the sponsor of the 2013 bill that created the majority of Colorado’s marijuana tax structure. He believes the public and even the pot industry might be amenable to more taxes, but they’d have to be for the right cause.

“I think voters saw through the veil on Prop 119,” says Singer, who now works part-time for marijuana consulting firm VS Strategies, which also employs Tvert. “It was a pretty complicated issue; it had a lot of moving parts. It took money from public education, created this new voucher program and also raised taxes. People saw through that and thought it looked like a complicated scheme that did more than one thing.”

Singer, who served with Johnston in the Colorado Legislature from 2013 to 2017, suggests that the former state senator and some of his allies might have had motivations beyond educational services for using a marijuana tax to fund LEAP. Webb and Owens also publicly criticized Coloradans for legalizing marijuana in the past, Tvert points out.

Both men appeared in a 2016 advertisement aimed at dissuading Arizonans from legalizing recreational marijuana, using misleading statistics about marijuana’s impact on Colorado.

“If I were a cynical prohibitionist, I would pick a worthy cause, pick a marijuana tax increase that would hinder the industry, and I would put in one of my own pet projects on top of it and sell it to the voters as free puppies for everybody,” Singer says. “I think they were trying to bat for the cycle and get three or four things done in one ballot initiative. I also think they really care about early childhood education. No one can doubt Mike Johnston cares about kids, even if we might disagree on how those things are.”

Johnston denies that he had ulterior motives for targeting the pot industry. But he recognized that public support for Prop 119 was beginning to dip in the weeks leading up to the election, and admits that “people were raising good questions” about LEAP.

“We were thinking about implementing this in a successful way to address those concerns. I think everyone agreed with the purpose. I think most of the questions were around the revenue source or structure of the program,” Johnston says. “We had seen this trend coming of real skepticism from voters around any taxes and, I think, a skepticism in government in general. And you saw it play out across the state and across the country in some ways on election day.”

Former State Representative Jonathan Singer helped craft much of Colorado’s current marijuana tax structure.

Evan Semón

Death and Taxes

Proposition 119 wasn’t the only marijuana-related proposal shot down by voters; measures involving cannabis were on local ballots across the state.

Denver voters rejected an initiative that called for an increase in the city’s recreational marijuana taxes to fund Initiative 300: Pandemic Research Fund. The proposal would have raised the 26.41 percent tax rate by 1.5 percent to fund pandemic research and public-response plans during pandemics.

According to proponents of the measure, the tax increase would have raised around $7 million annually for research by the University of Colorado Denver CityCenter, a partnership of CU Denver, the City of Denver and local businesses. Not that those institutions were behind the concept: According to a CU Denver spokeswoman, the school “did not initiate this proposal, is not involved in the campaign or signature-gathering process, and has not taken a position on this proposed ballot initiative.”

More than $540,000 was spent on Initiative 300’s campaign by Guarding Against Pandemics, a group registered in Delaware with ties to cryptocurrency investor Sam Bankman-Fried. Guarding Against Pandemics also funded lobbying for a failed $30 billion pandemic package in Congress earlier this year.

Denver City and County campaign finance administrator Andy Szekeres told the Denver Channel that this marked the first time an out-of-state entity had fully financed a city ballot initiative.

The initiative went down with less than 40 percent of the vote.

“Like 119, while these seem good on their face and it’s people trying to do the right things for the right reasons, it really becomes disingenuous,” says Nico Pento, vice president of external affairs for dispensary chain Terrapin Care Station. “I think there’s always going to be someone who wants to do some pet project, and instead of doing the hard work and going through the process and finding funding the hard way for whatever new project they want to create, everyone wants to go to marijuana.”

A former Republican policy director in the Colorado House of Representatives, Pento says this attitude extends to state lawmakers, as well.

“It used to drive me nuts when we’d be doing our comprehensive review of the budget, and in all the legislation with fiscal notes attached, they’d always default to the Marijuana Tax Cash Fund,” he says, calling it “a combination of other funds being spoken for, and laziness.”

Explains Pento: “As a legislator, it’s easy to make your case for your project, especially if it has something to do with mental health, substance abuse or criminal justice.”

Nico Pento was a Republican policy director in the Colorado House of Representatives before working for Terrapin Care Station.

Evan Semón

Competition Is Coming

Earmarking marijuana revenue for state projects could get harder as dispensary sales plateau in Colorado. After six straight years of annual growth, the 2021 marijuana sales total could fall below 2020’s high. And state budgeters and pot business owners alike expect slower growth as Colorado’s marijuana market matures and more states legalize.

Then there’s the possibility that Congress will take action and greatly expand the competition.

Although not considered likely to pass this year, current federal legalization proposals floated by powerful senators like Majority Leader Chuck Schumer include excise taxes on recreational marijuana production or wholesale transactions as high as 25 percent — which would be on top of the 15 percent excise tax Colorado already collects. As one of six states with an excise tax on wholesale transactions, this could put Colorado growers at a disadvantage if Schumer’s bill or similar legislation ever passes.

Singer and Johnston both say that back in 2012, when Colorado was looking at legalization, the prospect of federal taxation was low on the list of discussion priorities.

“We knew at that point that federal legalization was probably not coming down the pike any time soon. We have some very rudimentary guidance from the Department of Justice, but that was about not contributing to teen use or drug economies,” Singer remembers.

Singer believes the United States is still years from national legalization, and that any form of federal taxation on marijuana would then take additional years to implement if it’s in conflict with established state taxes.

Another bargaining chip between the marijuana industry and state and federal governments could be an IRS code from the ’80s intended to target cocaine traffickers. The tax code, 280E, bans deductions from businesses whose revenue consists of trafficking in controlled substances, which marijuana is still labeled under federal law. The lack of deductions results in marijuana business owners paying tax rates of nearly 70 percent in some cases. If 280E were eliminated, that would theoretically free up some money for marijuana business owners.

“If I’m a cannabis business owner, would I trade slightly higher taxes for assurances like tax deductions, getting a bank loan or not going to jail? There’s a certain tradeoff or push-and-pull going on there,” Singer says.

Polis alluded to as much in a letter he sent to Congress in September, asking to eliminate 280E. He also recently suggested that Colorado eliminate the state income tax in favor of taxing certain polluting activities, however, and he wouldn’t rule out the idea of including marijuana as a polluting activity.

“The tax burden marijuana businesses and workers face will go down substantially, so it dwarfs any small change if the state is looking at 3 or 4 percent here, increase or decrease,” Polis said. Although his relationship with marijuana business owners has been rosy up to this point — and he was a strong proponent of the cannabis industry while he was in Congress — Polis’s endorsement of Prop 119 surprised his allies in the pot trade, who aren’t eager to see additional taxes any time soon.

“I do think we’re years away from federal legalization, but we hope there will not be future attempts to tax cannabis,” says Native Roots’ Fender. “I think we’re closely approaching the point where cannabis taxes are unsustainable for the consumer, especially in light of federal legalization. When you combine what’s happening at the state and local levels and the federal level, we are really worried for the long term, and we’re interested in making sure all of those things balance out.”

Colorado House Bill 1301, a successful 2021 measure that loosened outdoor growing laws for commercial marijuana, included language that required the MED to examine existing rules and tax laws for recreational marijuana’s wholesale cultivation market in an effort to stay competitive if marijuana becomes legal under federal law. During an October 18 committee meeting on HB 1301 tax provisions, VS Strategies suggested replacing that excise tax with…more sales taxes.

“We don’t want to put the state in a position where they’re not going to be receiving this,” VS Strategies associate Bia Campbell said during the meeting. “To me, the answer to that is through sales taxes.”

Be the first to comment