The Haymaker is Leafly Senior Editor Bruce Barcott’s opinion column on cannabis politics and culture.

A couple months ago legislators in Washington state removed the word marijuana and replaced it with cannabis in the state’s legal codes.

The bill’s authors did so because “the use of the term ‘marijuana’ in the United States has discriminatory origins.” They deemed the term cannabis more scientifically accurate.

But then the primary author of the new law made a bolder statement. “The term ‘marijuana’ itself is pejorative and racist,” state Rep. Melanie Morgan said. “It was used as a racist terminology to lock up Black and brown people.”

A lawmaker claimed the word marijuana ‘is pejorative and racist.’ But is it really?

Morgan’s “pejorative and racist” comment sparked a conversation about our use of the word at Leafly. We take language seriously here. We’re all too aware of the power of words to shape debate, create stigma, pass laws, and deny personal freedoms—especially when it comes to cannabis. Words can heal and words can harm.

We’ve long known that marijuana has a complicated history. But is it actually pejorative and racist?

Over the past few weeks I asked cannabis experts and my own Leafly colleagues for their input.

It turns out there’s no easy answer to the question. During our conversations, it dawned on me that we get into trouble when we demand a binary answer to a nonbinary question. We ask: “Is this word offensive?” But in most cases language doesn’t work like that. Words live, breathe, and evolve in an atmosphere of cultural context.

So let’s dive into the context of marijuana.

Origin of the word

Historian Isaac Campos, author of the book Home Grown: Marijuana and the Origins of Mexico’s War on Drugs, is the leading authority on the origin of the word. He traces it to botanists conducting research in Mexico in the 1850s. Those early naturalists noted that the local population had taken to calling the plant previously known as pipiltzintzintlis by a new name: mariguana. That word, Campos noted, would go on to “conquer the lexica of most of the Western Hemisphere.”

David Downs, Leafly’s California bureau chief, tipped me to Campos’ book. “Marijuana is an authentic indigenous Mexican term that has cultural and historical validity from the 1800s through the present day,” Downs said, “even if others abused it for political aims in the 20th century.”

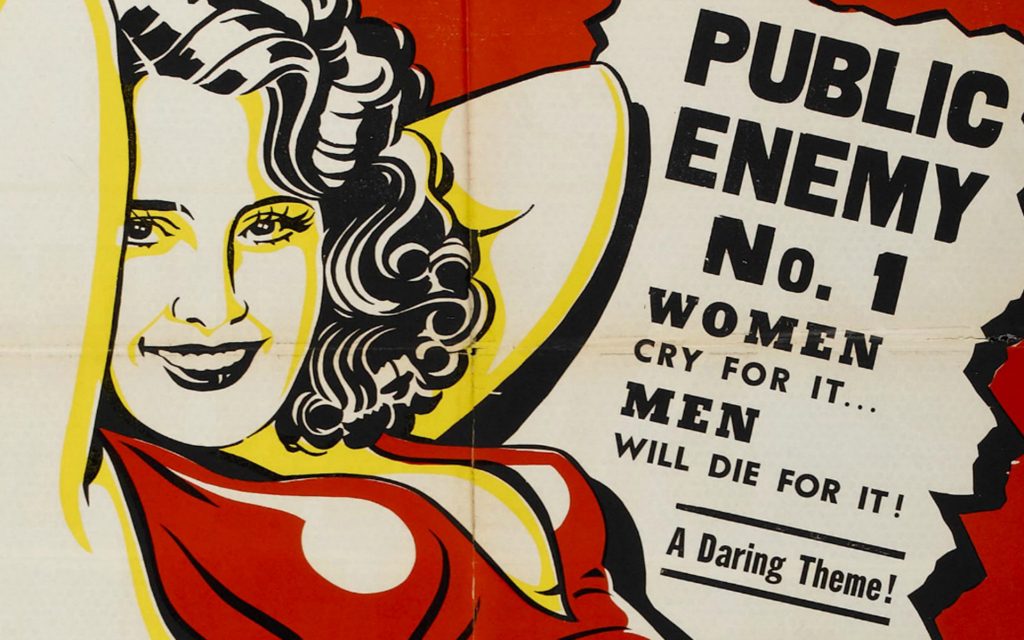

1930s: Demonizing the plant with a word

Marijuana held few negative connotations until the 1930s, when prohibitionist crusaders like Harry Anslinger, working with the Hearst newspaper chain, used it to demonize what had previously been known as hemp or cannabis.

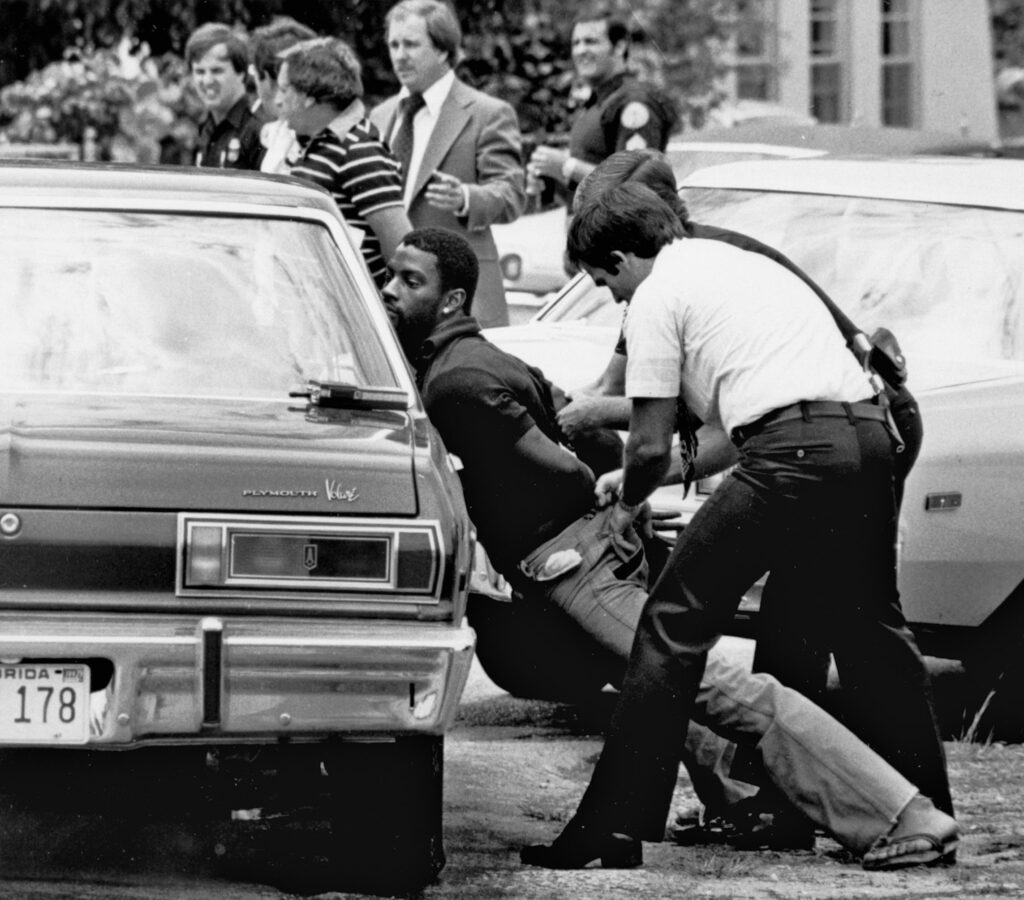

By calling it marijuana, Anslinger meant to cast a menacing, xenophobic shadow over good old patriotic hemp. And let’s be clear: By calling it marijuana, the intent was to frame cannabis as a dark-skinned threat to notions of white American innocence and purity.

Queen Adesuyi, senior national policy manager for the Drug Policy Alliance, noted that the word didn’t originate as an anti-immigrant slur. “The word marijuana was not originally created to stigmatize the plant,” she told me. “Rather, it was used in a political way to stigmatize the plant and the people associated with the plant. Where we see the actual harm of the use of the word marijuana is in the federal legal code, because it was intentionally used to align the plant with Mexicans, and Mexican-Americans, in order to incite xenophobia and bigotry. But the word itself is not a slur.”

Who’s speaking? What’s intended?

Before we spoke about the word, Adesuyi prefaced her remarks by making something clear: “I am not a Latina,” she said. “I am a Black woman, a first-generation Nigerian-American. I want to put that on the table as we navigate around the complicated history of this word.”

As with so many problematic words, the cultural position of the person uttering the word carries meaning. “We’ve got to consider who’s saying marijuana and why,” David Downs observed. The meaning of the word is bound up in the cultural position of the speaker, along with the speaker’s intention—whether to celebrate, describe, or slur.

Perhaps the most clarifying example of this dynamic can be found in the word queer.

A generation gap in language, experience

In 2019, researcher Juliette Rocheleau conducted an investigation into National Public Radio’s use of the term queer, which had been reclaimed by LGBTQ leaders in the 1990s, starting with the activist group Queer Nation. For decades, the word had been used as a hateful slur against LGBTQ people. Today it’s been largely normalized as the Q in LGBTQ.

Rocheleau found that—as with marijuana—speaker, intention, and context mattered. Even within LGBTQ circles, opinions often varied depending upon the generation of the person asked. Those in their early 20s were largely comfortable with the term—even self-identifying with the word—while many of those over 50, who may have experienced personal harm caused by the word, tended to avoid the term.

Geography and cultural context also matter. Queer spoken in celebration at a drag show in Seattle has a much different connotation than the same word used as an insult at a college frat party just a few miles away.

What is the word communicating?

Words are symbols for the objects and ideas they signify. In 2022, most of the English-speaking world still takes marijuana as the first word that comes to mind when referencing the cannabis plant or its products.

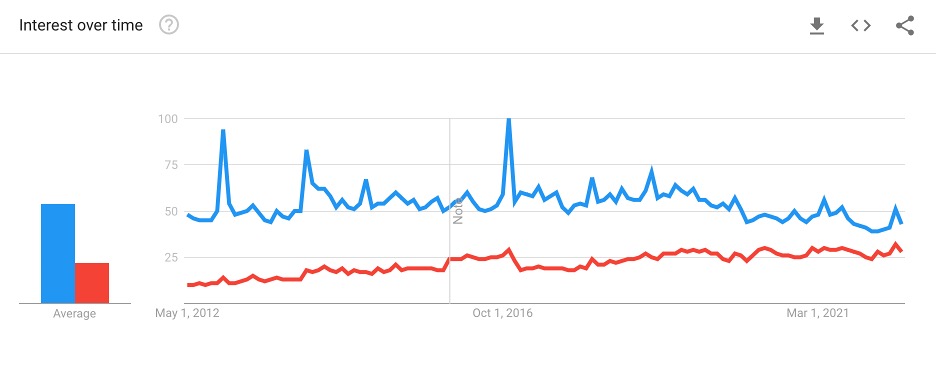

Although cannabis has become more common over the past decade, the Google Trends graph below shows marijuana still maintaining a clear edge over cannabis in search traffic. When people have a question about marijuana, they tend to look under marijuana first.

Google search trends

(blue = marijuana, red = cannabis)

The real role of SEO

At Leafly, we adopted a strict cannabis-first policy back in the early 2010s. We almost always used cannabis, never marijuana. Back then, saying cannabis counted as a political act. The word felt awkward in the mouth. It could come off as pretentious. More than once I found myself pausing before uttering it, as if it took an extra ounce of willpower to push it out. At the time, we did it to fight stigma and encourage the world to view “pot” in a new way. To take it seriously. To give the subject its dignity. Saying cannabis invited the listener to join the post-prohibition era.

We’re still cannabis-first, but over the years Leafly’s house style has relaxed in response to the realities of the world. We prefer cannabis, but we’ll also mix in marijuana, sometimes weed, and very occasionally pot.

We use those terms because that’s how people search for the information we publish. SEO (search engine optimization) is the practice of shaping headlines and articles with an eye toward connecting with people searching for information—and it matters. Appearing first in a Google search can mean the difference between reaching 1,000 readers or 100,000 readers.

While we seek to steer the world’s cannabis discussion in positive directions, we also want to meet our readers where they’re at—and connect them to the information they need. We might wish everyone searched for cannabis, but an equal number, or more, search for marijuana.

Usage doesn’t mean it’s not offensive

The fact that a word is currently in common usage, of course, doesn’t mean it should continue in common usage. Offensive words can and are dropped faster than you might expect, as fans of the NFL team based in Washington, DC, can confirm.

And search engines themselves aren’t perfectly neutral machines. Google employees tweak and update the company’s algorithms constantly. Employees are human, and Google is not an objective mirror—it is a $200 billion advertising platform. As Safiya Umoja Noble noted in her book Algorithms of Oppression, humans are fallible creatures with variable biases, prejudices, incentives, and blind spots.

“Rendering web content [pages] findable via search engines is an expressly social, economic, and human project,” Noble wrote. That project originates in a cauldron of human judgment, but because it’s expressed in programming code, she noted, it’s “naturalized as ‘objective’” when in fact it is not.

It’s NORML to use the word

NORML Deputy Director Paul Armentano is one of America’s foremost authorities on marijuana history and policy. He’s given the marijuana question a lot of thought, in part because it directly affects the success or failure of NORML’s work. The word also functions as the cornerstone of his organization’s name, the National Organization to Reform Marijuana Laws.

“NORML’s core mission is to influence public opinion and to change cannabis policies,” Armentano told me. “I’m not aware of any data showing that replacing the term ‘marijuana’ with ‘cannabis’ in our outreach or advocacy puts us in a better position to achieve those goals.”

“Despite the evolution of the public’s understanding of the cannabis plant, ‘marijuana’ still remains the terminology that both the public and elected officials are most familiar with at this point in time,” he added. “It also remains the more prevalent term in the scientific literature.” Armentano pointed out that a PubMed search of marijuana studies returned 40,144 results, while cannabis found 28,366 results.

Don’t whitewash our history

Queen Adesuyi, senior national policy manager for the Drug Policy Alliance, brought up another aspect of marijuana usage. That is: Labeling marijuana as racist or offensive may alienate many of the people most connected to the plant—and those disproportionately targeted by the War on Drugs.

“The word cannabis is very disconnected to most communities,” she said. “Your average person does not refer to the plant as cannabis.”

“As we’re working to advance legalization across the country, what we don’t want is a complete whitewashing of the history of marijuana criminalization and the impact that’s had on people of color,” Adesuyi added. “This is something we’re seeing the industry do. There’s an active attempt to revamp what the plant means, and who it represents.”

“When you think about ‘the new face of cannabis’” presented by some companies, she said, “it oftentimes is not in alignment with [those most affected by] the stigmatized and criminalized history of the plant.”

Unintentional consequences may arise

Adesuyi’s observation struck close to home. Back in the day, Leafly played a role in the “soccer mom-ization” of weed. It was an effort to disconnect the “new world of legal cannabis” from the “bad old days of illegal marijuana.” White, upper-middle-class suburban women were seen as the ideal welcoming face—and massive customer base—for the emerging legal industry.

That didn’t go so well. The target demographic did not swap wine for weed, and after a while my colleagues and I realized our pages were becoming a pale parade of white people. Cannabis sales data, and the evidence gathered by our own eyes in the field, told us we were shutting out a wide and diverse swath of cannabis consumers. We adapted and evolved.

“A huge number of people still use marijuana,” said Pat Goggins, a fellow editor at Leafly, “and I’m not sure cutting the term out of our vocabulary is practical, or the answer. Would that just be covering up the past?”

Must we always bend to tradition?

Janessa Bailey, Leafly’s culture editor, offered a perspective I hadn’t considered. “I’ve used the word cannabis around older generations and have been met with a puzzled look,” she said, “whereas marijuana seems to get the meaning across.”

“This makes me think about America as a gerontocracy—and how we do a lot of things in our country because it’s what older generations understand, even if it’s not progressive or forward-thinking. We entertain many outdated concepts simply because the people who grew up with those concepts continue to stand firmly in them out of a sense of tradition.”

Don’t waste energy arguing over words

There’s also the question of political focus and wasted resources. “It’s important to lead the public discussion about the terms we use,” said Calvin Stovall, Leafly’s East Coast editor, “but I don’t think it’s productive to police how consumers or other members of the industry use the word marijuana.

“I’d rather see us direct our collective energy at the institutional level—to change the laws that are racist and offensive. Forcing people to take a political stance by only saying cannabis and never marijuana creates a dynamic where the legalization community gets caught up arguing among ourselves about terminology.”

Decision time in Word Court

After weeks of conversation and rumination, I find myself disagreeing with Rep. Melanie Morgan.

Let me say it clearly: Marijuana is not pejorative or racist.

The impulse that drove Morgan to change the language of Washington State law wasn’t unfounded, though. It’s time to update the legal conversation to cannabis. But Morgan’s diagnosis was imprecise and too simplistic. Marijuana is a problematic, complicated word with a problematic, complicated history. In the year 2022 it exists in a state of flux, loathed by some while used without malice by many.

Thriving in the cannabis world requires flexibility and quick adaptive reflexes. The language we use reflects that. We’re constantly reading the room to determine the appropriate verbiage. Mostly it’s cannabis or marijuana, but now and then it’s weed and sometimes it’s pot. Sometimes it can feel like living in a Key & Peele code-switch sketch.

That’s my answer today. Stay tuned. It’ll probably change, because language never stops evolving and neither should we.

By submitting this form, you will be subscribed to news and promotional emails from Leafly and you agree to Leafly’s Terms of Service and Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe from Leafly email messages anytime.

Be the first to comment