Video posted this morning by the Institute for Justice which features three local abatement cases previously covered by Redheaded Blackbelt.

This morning, The Institute for Justice (IJ) in partnership with abated local landowners (featured earlier in articles on Redheaded Blackbelt) filed a class-action lawsuit against Humboldt County. The nationally acclaimed, non profit, human rights law firm filed the suit on behalf of all 1219 Humboldt County cannabis abatement recipients, which they claim have been the victim of “The County’s code enforcement policy [that] is designed to squeeze every dollar it can from legalized marijuana, often at the expense of innocent people.”

The suit was served to the following:

COUNTY OF HUMBOLDT, CALIFORNIA; HUMBOLDT COUNTY BOARD OF SUPERVISORS; HUMBOLDT COUNTY PLANNING AND BUILDING DEPARTMENT; VIRGINIA BASS, MIKE WILSON, REX BOHN, MICHELLE BUSHNELL, and STEVE MADRONE, in their official capacity as Supervisors of Humboldt County; and JOHN H. FORD in his official capacity as Planning and Building Director.

The Institute for Justice is holding a live press conference today via Zoom at 11 a.m. (click here) in which they will further explain their suit. They are encouraging all abatement victims and concerned community members to join them.

The plaintiffs call the satellite cannabis abatement program “a coercive land grab,” “a maximum pressure campaign,” and “an extortive death blow” to property owners. Innocent landowners, nuns growing vegetables, personal medical cultivators, low income housing developers, lavender farmers, fire departments and volunteers have all been rolled up in what the plaintiffs term a “regulation-for-profit racket.”

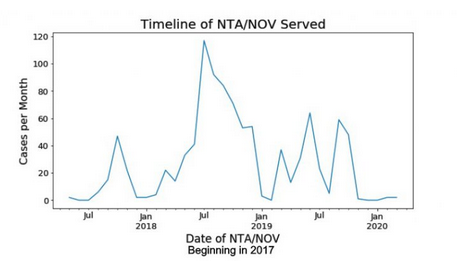

Notices distributed until Jan 2020. [Chart created by UC Berkeley Cannabis Research Center]

The Humboldt Environmental Harm Reduction (HEIR) program, better known as the satellite cannabis abatement program, is overseen by the Planning and Building Department’s Code Enforcement Unit (CEU) which now dominates the enforcement of cannabis laws, and has extracted millions in fines and penalties primarily from rural residents in Southern Humboldt’s District Two (70%), Northern Humboldt’s District Five (17%), and Mid-West’s District One (10%).

The lawsuit reads in part,

The County’s conduct toward the Plaintiffs is part of a broader policy and practice, pursuant to which the County cites landowners for enhanced cannabis-related code violations without regard to probable cause, fails to schedule administrative hearings at a meaningful time and in a meaningful manner, imposes unconstitutional conditions on permits for those properties, imposes unconstitutionally excessive fines and fees, and denies accused landowners the right to a jury of their peers to decide factual questions that determine whether the Plaintiffs owe hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of dollars in fines. (link to full lawsuit filing)

Only months after legalization in June 2017, the cannabis abatement code changes were made by County staff, okayed by County Counsel, and voted on by the Board of Supervisors at the time; Mike Wilson, Estelle Fennel, Rex Bohn, Virginia Bass, and Ryan Sunberg. These code changes that took effect in 2018, allowed for $6,000-10,000 in daily fines, per violation for unpermitted commercial cannabis cultivation and affiliated charges, such as structures without permits, grading of more than fifty cubic yards, or developments within streamside management areas, with smaller penalties for unapproved septic systems, junk cars, living in RVs, and more.

The lawsuit describes the program’s inconsistency, stating, “By alleging that code violations relate to illegal cannabis cultivation, the County exponentially increases the fines for those violations, regardless of whether the violation poses any harm to the community.”

The program itself has changed the community as well. Pre-Proposition 64 there was an estimated 15,000 black market cannabis farms, also known as the traditional market. Since cannabis became legal, the number of traditional market farms has dwindled to 3,000-5,000 according to Humboldt County Sheriff Billy Honsal when he spoke to us in an interview earlier this year. In addition, Sheriff Honsal explained that of the approximately 1,000 permitted farms, only 75% were operating this year. That means an estimated 32% of the original farms are left since legalization. However many of our permitted farms are new, so that means less than 32% of legacy operations remain today.

Jared McClain [Screenshot from video]

“We filed this class action to put an end to Humboldt’s abusive code-enforcement regime. The County issues life-ruining fines to innocent people without proof or process,” says Jared McClain, lawyer at IJ heading the suit.

Attorneys Joshua House, Jared McClain, Rob Johnson, of IJ, are filing the federal class action lawsuit on behalf of all cannabis abatement victims, in addition to Thomas V. Loran III, and Derek M. Mayor of Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pitmann in San Francisco and Sacramento. The attorneys claim that what Humboldt County has been doing to property owners is unconstitutional according to the Fifth, Seventh, Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments, that in short ensures the right to trial by jury, due process of law, and the right to prohibit government’s excessive fines, fees and forfeitures.

The suit reads in part:

Humboldt County fines landowners hundreds of thousands of dollars for things they never did because it doesn’t investigate the charges it files. The accused rarely ever get the chance to defend themselves…While the County makes accused landowners wait indefinitely for an administrative hearing, fines continue to accumulate and the County denies them permits to develop their property. The only way out is to pay the County, one way or another.

Type of Class Action Suit

The Institute for Justice is renowned for their work advocating for residents across the country who are experiencing heavy handed, unconstitutional government actions, which they coin “policing for profit” and “regulation for profit.”

This particular lawsuit is a class-action suit, which is a civil lawsuit brought on behalf of a group, in this case who have suffered common injuries as a result of the county’s conduct, with Plaintiffs acting to represent the whole group of abatement recipients.

Essentially this case is not-for-profit, where the plaintiffs represent all abatement recipients, they do not have to pay for IJ’s counsel and the attorneys are not monetarily compensated by them. The named plaintiffs say they view it as “a community service” that they are proud to participate in on behalf of the whole county and beyond.

One of the leading attorneys on the suit Mr. McClain explains this suit is a,

23(b)(2), [which] means we’re only seeking forward-looking injunctive and declaratory relief on behalf of the class. No damages. Injunction is ordering the county to do something or not do something. Declaration is saying that they’ve violated the law. So we’re asking the court to say the county violated the rights of everyone in the class and to enjoin/stop them from doing so anymore. Basically we’re asking the court to say the county’s cannabis-abatement program is unconstitutional and order them to stop enforcing their laws in ways that violate the rights of our clients and the class.

The plaintiff’s reward for a win is policy changes that could positively impact all HEIR cannabis abatement recipients, and may even potentially ripple out to help revive the struggling Humboldt economy. If they win, it will make it easier for other abated property owners who feel wronged by Code Enforcement, to bring their cases forward thereafter. Given the case is being filed in Federal Court, the effects could potentially impact residents nationwide as well who are enduring similar regulatory tactics by state and local governments.

McClain details the Humboldt County Clients are, “Four examples of the innocent people who the County’s indiscriminate enforcement policy has harmed.”

The Humboldt County property owners leading the class action federal suit, have all been featured in stories by this reporter on the RHBB news site. The plaintiffs are District Five’s Rhonda Olson, and District Two’s Corrinne and Doug Thomas, in addition to Blu Graham, who was the very first abatement victim to speak out publicly in 2020 on RHBB (anonymously at the time) about his case. Today, Graham goes public with his story and explains why he volunteered to participate in the class action lawsuit against the County.

Blu Graham

Blu Graham [Screenshot from the Institute for Justice]

Blu Graham, a hardworking family man, now a grandfather, owns and operates two small businesses including a hiking tourism company Lost Coast Adventure Tours, where he escorts travelers through the breathtaking Lost Coast Trail and expansive CA redwoods. He also owns a restaurant with his wife called Mi Mochima that overlooks the stunning Shelter Cove coast and dishes up their Humboldt homegrown, Venezuelan recipes Friday- Sunday.

In May 2018, the same day seven of his neighbors received an abatement, Graham also received a notice citing three alleged violations, grading for the purpose of cultivating cannabis, cultivation itself, and unpermitted structures, or hoop houses in this case. The abatement initially came with a $30,000 daily fine for 90 days, or 2.7 million dollars.

(Notices distributed until Jan 2020, chart created by UC Berkeley Cannabis Research Center)

His hoop houses were empty, and Graham did not “grade for the purpose of cannabis cultivation,” as stated on the notice, so he assumed the mistake could be easily resolved with a visit to the Planning and Building Department.

Graham was incorrect.

Graham explained that he went to Code Enforcement immediately to declare his innocence detailing, “I got abated on Thursday, I went into Code Enforcement the following Monday.”

Graham said he met in the main office of the Planning Dept. in public with permitted farmers, “who were going through hell.” Graham added, “I was going through hell right alongside them, with all these moms and grandmas who were coming in crying about their abatements.”

In order to prove he had no cannabis in his hoophouses or on his property, Graham paid for his own satellite photos during the week the abatement notice was posted, but Code Enforcement Officers John Meredo, Warren Black, Brian Bowes and later Bob Russell continued to deny his innocence and he was unable to get a meeting with Director Ford for years.

Graham said, “I told the county I have nothing on my property…I invited them to come inspect it that day to see for themselves, which they refused….they said I had to sign a compliance agreement.”

The suit describes Graham’s three options given by the county, stating, “Settle, appeal, or lose his land. They tried to persuade Blu to take the first option—enter a settlement agreement under which he’d admit guilt and pay a $30,000 fine to the County.”

Graham said the initial “compliance agreement,” which more accurately should be called a “settlement agreement” according to the Institute for Justice, also required him to hire an engineer, tear his hoop houses down, and fill in his rain catchment pond used for livestock, wildlife and in case of fire.

This was unacceptable to Graham because he said he was innocent.

Graham actually used the hoophouse to cultivate fresh produce for his restaurant and had both a nursery and producers certificate to do so. When he applied for the greenhouse structures in 2014 he claims no one in the Planning Department told him he needed a $150 agricultural exempt permit, which may be due to the policy changing after that with no notice to him.

Graham asked Code Enforcement Officer Brian Bowes for proof he was cultivating cannabis, Bowes allegedly told Graham, “ We don’t have any proof, but you weren’t just growing asparagus in there.”

Attorney McClain explains the county’s policy has no regard for probable cause. McClain said,“The County accuses anyone with a greenhouse or garden plot of growing marijuana without a permit and forces them to prove their innocence at a hearing the County never provides. People have a right to grow food on their land without having to prove to the government that they aren’t growing marijuana.”

The suit also detailed, “The County then imposes ruinous daily fines for things like the failure to get a permit before building a greenhouse if the County thinks a landowner might have marijuana inside the greenhouse.”

“We are entitled to have greenhouses and to grow our own vegetables, but according to [Code Enforcement], if you have a greenhouse, you are a criminal, and I don’t agree with that,” Graham argued.

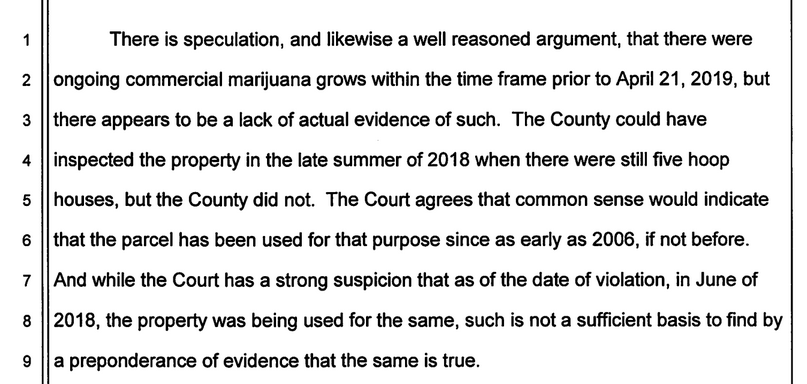

Although a large number of abatement recipients were cited for growing cannabis commercially as a direct result of satellite photos showing only a hoophouse, Humboldt County Superior Judge Kelly Neal ruled in 2021 that a greenhouse is not “actual evidence” of cannabis cultivation.

(A screenshot of a 2021 appeal of an appeal hearing at the Humboldt County Superior Court, where Judge Kelly Neal ruled greenhouses are not “actual evidence” of cannabis. Note: This case is not related to the plaintiffs or IJ lawsuit.)

Similarly, logging legacies, and fire fuel breaks do not constitute grading violations, as was also alleged in Graham’s case.

Graham is highly aware of fire dangers in Northern California because he has been a volunteer firefighter since he was nineteen years old. He was the Whale Gulch Volunteer Fire Company Chief for four years and he remains a Captain there today.

Graham’s ridgetop was used as a fire fuel break to stop the Finley Creek Fire that took out Shelter Cove in 1973 and threatened the forest before stopping on his ridge. Graham’s “grading” allegation was for his fire prevention efforts including the fuel break maintenance, brush clearing on an old logging flat, and his installing of a rain catchment pond, which he had inspected and approved by the environmental organization Sanctuary Forest. This is technically a grading violation with a maximum penalty of 1,000 per day when not connected to cannabis cultivation, and in some cases it can be resolved with a retroactive permit.

Currently the County offers low cost agricultural permits for ponds such as his, however, Graham said that no one in Code Enforcement mentioned this as a resolution to Graham in the over four years his case was left unresolved.

Graham said, “The state of California is burning down, we need as much water storage as we can get ….so I basically got abated for being ahead of the game.”

Right to a Jury and Due Process of Law

One of the issues in this lawsuit is the lack of a jury trial, in addition to the demanding timeline, which IJ deems is unconstitutional, for it violates one’s right to due process of law. When property owners receive an abatement notice, they are given only ten calendar days to resolve the violations where applicable, and apply for an appeal hearing with Code Enforcement. The initial fines threatened to be applied daily, almost always exceeding the value of the property if applied for 90 days, so tensions are high.

“The Planning and Building Department has run wild with its new fine-driven mandate and adopted a policy and practice of charging cannabis-related code violations without proof or process,” The lawsuit says.

Some abatement recipients wait for years without due process after they file for an appeal hearing, while worried they will lose all they have.

Cannabis Attorney Eugene Denson, who specializes in abatement cases, questions the validity of the appeal hearings which he calls a “kangaroo court.”

Denson says, “The hearing officer is an out of town lawyer who acts as a judge, and is contracted by the Director of the Planning Dept. John Ford.”

Denson points out that Ford oversees the abatement program afterall, and who wants to upset their boss?

McClain added, “County officials brag that the administrative judges they hire have never ruled against the County. That’s why every American has a right to a jury of their peers.”

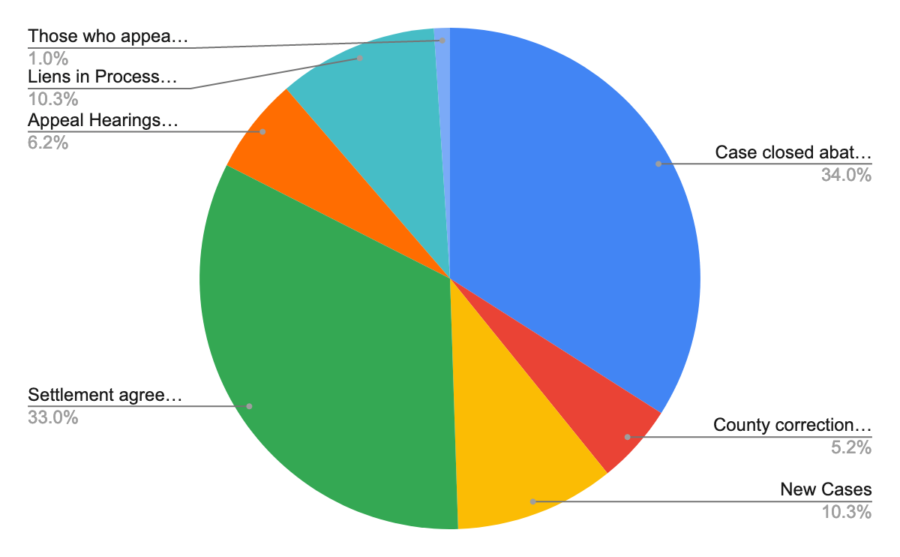

Of the approximately 6% of appeal hearings held so far in four years, all decisions have gone in favor of the county, though a handful or 1% have been appealed to the Humboldt Superior Court (Note: This may not include appeal hearings that were labeled “historic” prior to a system update in the summer of 2019).

Given Code Enforcement’s “data migration to new dept. software in the summer of 2019” there are 313 cases labeled “closed historic” without other case status details. Percentages listed will reflect the 906 abatements remaining, instead of 1219, which have status details listed, to get a more accurate picture of current case status.

(Notices distributed until Jan 2020, chart created by UC Berkeley Cannabis Research Center)

New cases continue to add up, with 10% of abatement recipients listed as just receiving a notice or are in various initial phases of the process. While property owners have extreme fines and strict timelines, the county does not have any timelines set for themselves to resolve cases or bring them to an appeal hearing. Subsequently, Code Enforcement is at a virtual standstill at moving through requests for appeal hearings, with about 6% in limbo, sometimes for years, such as Graham.

Despite his having applied for an abatement appeal hearing in the ten day window that recipients are allowed when they are given an abatement, for over four years Graham was denied his right to his appeal hearing, and left worrying he could potentially owe $30,000 a day, every day since May 2018. This has not only been financially devastating but caused his family immeasurable stress.

Graham compared the abatement program to a “mob shakedown” and added, “I feel like they are strong-arming people. [At 30,000 a day ] I must owe them, a billion dollars by now …and so what are they going to do, take my home? Do they want people who work hard for this community sleeping under bridges?”

Graham said even though he was innocent and complied with the county’s demands, nothing he did could convince Code Enforcement to resolve his case or get him the appeal hearing he requested, that is until last month, a couple of weeks before the lawsuit was filed. Graham finally received a notice declaring his appeal hearing was scheduled for Oct 14. Because he accepted a settlement offer (detailed later), the hearing is being canceled, and, Graham said after negotiations with Warren Black, he felt it was more likely another tool used by Code Enforcement to get him to sign a settlement agreement.

This wasn’t the first time he felt forced to sign. Since 2020, Code Enforcement held up Graham’s Safe Homes permit approval “as ransom” he felt, in exchange for his signing the settlement agreement, despite his applying and paying for the retroactive house permit years ago, meaning his home was at stake.

Additionally the suit details how the County bypassed Graham’s legal counsel throughout the negotiation process, stating,

“Mr. Black encouraged Blu to submit public-records requests to see the County’s perfect win-rate in administrative hearings…Blu interpreted this email as telling him he should settle his case because Code Enforcement does not lose at its administrative hearings… Mr. Black emailed Blu again on August 4, 2020, and confirmed that he would only “release the hold on [Blu’s] safe homes project” if Blu settled his abatement case.”

The suit continues, “Shortly after the County served the notice of administrative hearing, Mr. Black once again contacted Blu directly to pressure him to settle.”

The negotiations were ongoing for over four years. After Code Enforcement demanded $30,000 a day from Graham in penalties, a $30,000 flat fine was later offered, then $20,000, then $10,000, and finally a no-penalty settlement agreement. After that, the word cannabis was removed from the agreement, and only the rain catchment agricultural pond was cited, indicating Code Enforcement acknowledged they had no evidence of cannabis cultivation.

The lawsuit details more about how County residents found themselves in this situation, explaining,

Once marijuana became legal, a newly constituted Code Enforcement Unit was in place to aggressively enforce code violations in Humboldt County. …The County knew there were plenty of code violations due to its underenforcement of the code for decades. Indeed, just as the County implemented its cannabis-driven code enforcement, it also created a “Safe Home Program,” under which gave landowners from October 2017 through the end of 2022 to come forward and apply for as-built permits for their property without facing penalties…So, while the County dangled the carrot of amnesty for building code violations, its Code Enforcement unit began blindly swinging the stick of ruinous fines at any violation with a perceived nexus to cannabis.

Graham kept professing his innocence and working to comply, and said, “At what point is this just a fear tactic? They are basically saying, pay us money or we’re going to hammer you.”

The suit details how Graham’s case violates his rights, stating, “The County’s refusal to schedule a timely administrative hearing forces an accused landowner to endure years under the threat of fines, fees, abatement costs, and leaves the landowner unable to develop their land with no guarantee that the County will ever schedule their hearing…Fully aware of the financial and psychological costs brought to bear by its abatement regime, the County routinely checks in with landowners to ask if they still want a hearing while pressuring them into settling their case instead.”

The lawsuit aspires to bring relief for cases like Graham’s. It requests the court to,

“Declare that the County’s cannabis-related code-enforcement policies and practices violate the procedural due process guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment…Plaintiffs respectfully request that this Court: Certify a class under Rule 23(b)(2) consisting of: “All persons who are currently facing penalties for cannabis-related Category 4 violations that were levied after January 1, 2018, who filed an ‘Attachment C’ to request an administrative hearing within 10 days of the County effecting service, and who have still not received a hearing for their appeal.”

This means people who have requested appeal hearings but have not received them yet and who have not settled yet are part of this class action. IJ reports they are happy to speak with anyone who has an active abatement against them.

On September 26, Graham’s abatement finally came to a close he felt because District Two Supervisor Michele Bushnell arranged to meet with him, Director John Ford, and Code Enforcement officer Bob Russell.

The meeting aimed to retroactively resolve Graham’s unpermitted rain catchment agriculture pond, the basis for his pending abatement in order to avoid the appeal hearing. An appeal hearing would not only have been costly and time consuming for the county, but for Graham, it would have added more years of stress and legal fees, in addition to possible penalties of $1,000 a day for 90 days, or $90,000.

The suit details Graham’s resolution stating, “Director Ford agreed to drop Blu’s case without a signed settlement agreement if Blu paid over $3,700 in administrative fees and got the permit for the pond that Blu had been requesting since spring 2018… Director Ford accepted the engineering report Blu had submitted back in January 2019 to support his permit application…Blu completed the permitting process on Monday, October 3, 2022, and the County closed its case against him.”

The lawsuit adds, “Plaintiff Blu Graham was planning to be a class representative until the County suddenly agreed to dismiss his abatement order the week before filing.”

IJ’s Past Constitutional Lawsuit Regarding Excessive Fines, Fees, and Forfeitures

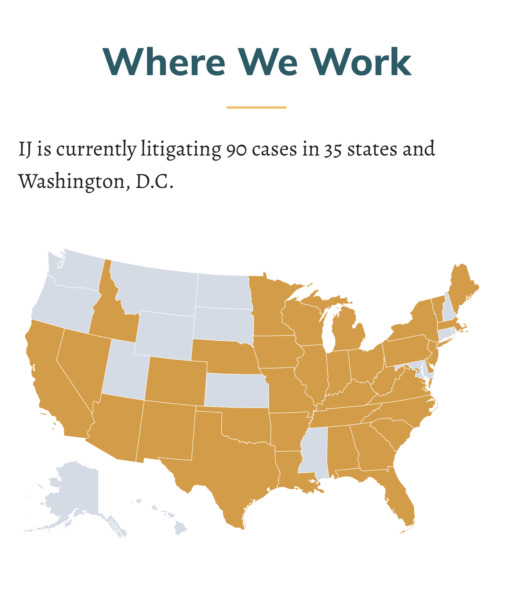

Founded over thirty years ago in 1991, The Institute for Justice has an expansive outreach with seven headquarters nationwide, and attorneys working in offices in most states.

Screengrab from Institute of Justice’s website.

Going head to head with the government isn’t the easiest area of law to practice, and win at least. Still, IJ’s case track record speaks for itself, having three in four wins of their more than 300 cases litigated, ten of which were before the Supreme Court.

In 2019 their Timbs v Indiana Supreme Court case unanimous ruling was authored in part by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg (RBG) about a year before she passed. In her ruling RBG wrote about excessive fines, fees and forfeitures, and the long history of their being used to eradicate certain groups of people by penalizing them for normal conduct.

RBG wrote in her decision,

“Exorbitant tolls undermine other constitutional liberties…Excessive fines can be used, for example, to retaliate against or chill the speech of political enemies…Even absent a political motive, fines may be employed ‘in a measure out of accord with the penal goals of retribution and deterrence,’ for ‘fines are a source of revenue,’ while other forms of punishment ‘cost a State money.’

In 2019, thanks to the Institute for Justice, The Supreme Court ruled unanimously the Eighth Amendment applied to not just the Federal governments, but also states, counties, and local municipalities, deeming excessive fines unconstitutional at all levels of government.

In her 2019 ruling, RBG detailed part of the history of excessive fines post slavery and it’s importance in maintaining our civil liberties.

RBG wrote,

Following the Civil War, Southern States enacted Black Codes to subjugate newly freed slaves and maintain the prewar racial hierarchy. Among these laws’ provisions were draconian fines for violating broad proscriptions on “vagrancy” and other dubious offenses…When newly freed slaves were unable to pay imposed fines, States often demanded involuntary labor instead.

Over the past five years rural Humboldt residents say they too feel unduly burdened by excessive fines for dubious offenses, extreme demands, heavy-handed enforcement, and even cite feeling targeted due to a prejudice against their community at a time when legalization promised to deliver liberation and legitimacy.

Rhonda Olson, another plaintiff featured in a recent RHBB series that got the attention of the IJ team, said, “ It’s ironic that after legalization the fines threatened for cannabis allegations, even if you are innocent, leave property owners dreaming of the days when you’d just go to jail vs face a fine of, in my case over 7 million— and for what, the crime of buying property, and trying to provide low income housing?”

Rhonda Olson

Rhonda Olsen [Screenshot from video]

After Olson purchased three properties to develop affordable housing she got an abatement notice on all parcels in the previous owners name for cultivation years prior to her purchase. Code Enforcement abated and red tagged her barn threatening $104,000 in daily fines, or $9.36 million total and demanded she sign a settlement agreement.

The new set of abatements given in her name reduced the daily penalties to $83,000, or $7,470,000.

Olson explained, “The county said they were going to work with me, and instead slapped me with a red tag on my barn and $83,000 in daily fines…They keep trying to get me to sign a settlement agreement and pay fines under duress— I refuse.”

The IJ suit states Olson faces daily fines that are nearly double her total purchase price of 60,000 and adds, “The County has also prohibited her from developing her property—the very reason she bought it—while her case is pending. She’s been waiting over two years for a hearing.”

The plaintiffs feel their concerns have largely been “met with crickets” by policy makers over the years. Olson explains she experienced “high pressure,” “bullying tactics,” but, “when we asked policy makers for help for years, no one helped us.”

Olson adds, “The stress of dealing with Humboldt county for almost two years made me physically sick [with shingles]. I think the abatement program was set up to do exactly that: bleed us of every dollar we have and make us go away. Well I’m here to stay, I’ve been lucky enough to get support from the Institute for Justice.”

The Scope: Farm Sizes, Violations Cited and Compliance Agreement Penalties

According to the 2020 Census, Humboldt County has a population of 136,101, and 54,140 households. When considering the 1,219 abatements in total, that’s a rough estimate of 1/45 households impacted by the HEIR program countywide.

That figure becomes more dire when considering that 70% of abatements were given to District Two, with a population of 26,778 according to the county’s district rezoning data featured on the Lost Coast Outpost. If household v. populations are applied evenly countywide (which they may or may not be), that equates to 10,652 households in District Two, meaning approximately 1/13 households have been directly impacted by this “unconstitutional” program in Southern Humboldt. This does not account for affiliated workers, family, friends who have been directly impacted either, not to mention the local economy.

UC Berkeley Cannabis Research Center Associates helped us analyze a records request response pertaining to abatements from Code Enforcement last month, to get an idea of settlement agreements signed, the scope of the fines paid, violations cited and size of the farms at issue.

Of the 1,219 abatement notices in total, the average farm size* alleged is 10,227 sq. ft. (*of the 59.77% of owners that have their square footage noted in the records request), with an average of 2.7865 violations cited each.

| Farm Size

*The following are based on the 59.77% that note their sq ft cultivated |

Average Violations Cited |

| *Avg # for farms <5k sq ft | 2.04961832 violations |

| *Avg # for farms <10k sq ft | 2.377871 violations |

| *Avg # for farms >10k sq ft | 3.57895 violations |

| *Avg # for farms >20k sq ft | 4.115385 violations |

Since legalization, medical cannabis laws have also been unclear within enforcement agencies (as discussed in a previous article). There is no way to know for certain how many of these abatement recipients signed compliance agreements and paid fines based on Code Enforcement’s inconsistent medical cannabis law understanding. So for example, some of the abatements under 5,000 sq.ft. with an average of 2.05 violations cited, could be hoophouses and medical gardens and/or vegetables.

“The crude satellite images that the County relies on reveal plenty of activity wholly unrelated to cannabis growth—let alone illegal growth in a state that allows residents to grow cannabis for medical and recreational use,” the lawsuit filing details.

Many notice recipients were terrified of the daily penalties threatened and so they followed the instruction of Code Enforcement and signed a settlement agreement, under duress, and paid a penalty, often for the amount of the daily fine proposed, $6,000-$10,000 for each alleged violation.

The lawsuit describes the HEIR program as a “pressure campaign…with the ruinous fines… designed to generate revenue for the County…Once a landowner receives an [abatement], they are trapped unless they pay the County to let them out.”

About 33% of noticed property owners have agreed to sign settlement agreements, and pay an average penalty of $15,509.05 for all farm sizes. In total, $3,858,000 in penalties have been contracted to be paid, with $3,513,503.56 of that collected so far, in addition to millions more in costs (unquantifiable) and administrative fees (not listed in the public records request).

| Size of Farm | Average Penalty* |

| Farms >10k sq ft | $19,327.01 |

| Farms <10k sq ft | $14,588.24 |

| All size farms | $15,509.05 |

| *Calculated using 59% of farms that note sq. ft. cultivated |

(Breakdown of average penalties compared with alleged size of farms)

IJ Attorney McClain explains, “The County’s cannabis-related code enforcement is designed to use excessive fines to pressure people into settlements without providing them due process. As the County makes innocent landowners wait indefinitely for their day in court, daily fines continue to accrue and the county refuses to issue permits they need for their property. This pressure is designed to force people into settlements. No one should have to incur thousands in fines just to get their day in court.”

The Thomases

![The Thomases holding their abatement letter. [Screenshot from the Institute of Justice's video ]](https://kymkemp.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/image2-2.jpg)

The Thomases holding their abatement letter. [Screenshot from the Institute of Justice’s video ]

Corrinne and Doug Thomas (discussed in previous articles), plaintiffs in the lawsuit, are also innocent buyers that felt forced to sign the settlement agreement under duress when they faced a $12,000 daily penalty for 90 days or $1,080,00, for a sizable storage shed they just purchased with their land. The county initially demanded they remove the structure as a result of the previous owner’s unlawful cannabis cultivation two years prior to their purchase.

“We signed the settlement agreement under duress, it was coercion,” said Doug Thomas.

Doug and Corrinne Thomas are retired fire refugees from Southern CA, world renowned for their literature, film and philanthropy work around autism. They have no connection whatsoever to the cannabis industry, so when they received their abatement notice last year alleging they were cultivating cannabis in their storage shed, they were not just perplexed, but terrified.

The county initially demanded they remove the two and a half story shed. According to their engineer, the demolition would have cost about $180,000, and would require them to remove approximately 70 trees, some Redwoods and old growth Douglas Firs, one of the main reasons they bought the property. Corrine said she felt the request was counterintuitive to the aim of the Humboldt Environmental Harm Reduction (HEIR) program.

Corrine explained, “New buyers… to Humboldt County, are not at fault, or have intent to break any Building and Safety Laws,” adding, “New policies must be established to determine Federal Constitutionality subjective to each owner. To establish a material fine that could render one homeless instead of first showing evidence that an owner is responsible, is neglectful, and may be illegal.”

March 23, the day after part one of their article was published a policy change was initiated by the Planning Dept. and approved by the Board of Supervisors, enabling the Thomases (and other property owners) to bring structure(s) once used for cannabis up to code instead. However this path is still costly. Though the estimated $11,000 cost to comply in the Thomases case is a significant improvement from the demolition estimate of $180,000, they still feel this is unfair.

Doug detailed the stress involved, and said,

I’ve had people say, ‘well the county didn’t actually take the million dollars, they just said they were gonna.’ But It’s a big stress, it’s like a guy pulling a gun on you until you give them your money, that’s what the county is doing. The whole premise of the program makes no sense, especially when you compare it to actual serious crimes like child abuse or violence happening in structures all over the county—how many of those owners are forced to destroy the affiliated buildings? The only crime I see associated with cannabis is not paying the county’s extortion fee…This is all about marijuana right, but the government has accepted cannabis as a legal activity—- but only if they get their extortion fee first. That needs to change.

The suit explains how the county has gone beyond their traditional role of protecting the safety, health and welfare of the public. It states, “The County’s proactive, cannabis-focused enforcement mandate extended the purview of the Planning and Building Department and its Code Enforcement Unit beyond the traditional role of processing permit applications and abating nuisances that pose a danger to the public welfare.”

This is indicated in staff increase since legalization. The suit reads, “In 2018, the Department’s first year prosecuting cannabis-adjacent building and permitting issues, the County increased code enforcement by about 700 percent, resulting in the County’s assessment of $3 million in fines that year.”

“The abatement policy has already brought economic deterioration to Humboldt County,” Corrine said, “Wages are low, industry and jobs are almost non-existent, population growth is low, new housing is nil. The public’s first impression of Humboldt County is that it is a low income area, even though the beauty is far superior. We would love to see businesses instituted that would provide jobs and income to provide first rate schools and opportunity for the current residents.“

Conclusion

In 2020 the HEIR cannabis abatement program received an award from the California Association of Counties (CSAC) for their “innovative and cost effective model to ensure compliance.”

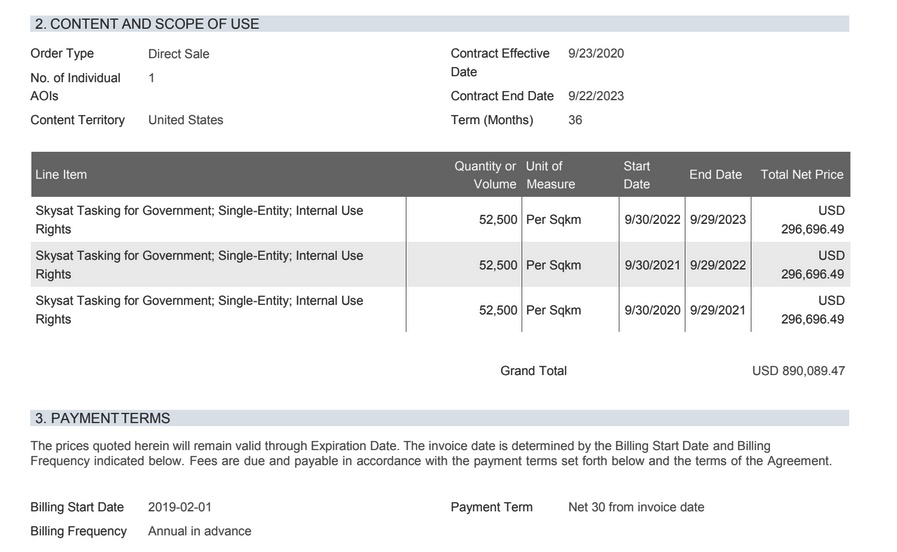

(Screengrab from PlanetLabs offer for satellite abatement contract obtained by a public records request)

It’s true— the program costs very little to the county with an annual cost of about $300,000 for the satellite contract itself, plus the annual Planning Dept. budget of $28.1 million, and in comparison to the millions it’s added to the General Fund since 2017. But it’s only “cost effective,” if one neglects to consider the cost to the community.

In 2018 Blu Graham asked Code Enforcement Agent Brian Bowes, “Of all the mega grows and crazy stuff going on in the county, why did they go after my little hippie homesteader community— Why us?”

Graham alleges Bowes responded, “Oh don’t worry, everyone is going to get one of these [abatements].”

It certainly feels that way in Southern Humboldt, Graham said, and speaks to the bigger impacts culturally and socioeconomically, explaining, “I want to promote our hiking trails here. I want to work to bring eco-tourism into our area which could bring life back to this community, but instead I’m dealing with an abatement. How many people in this community are in the same boat? This place is dying. Driving through Garberville there is an entire block of empty buildings and I blame Humboldt County for that.”

Doug adds, “The economy in the area has been destroyed by the county shutting down the cannabis industry, the restaurants, the shops, hardware stores, motels, the whole economy was impacted … We are not going to agree to anything except for the county to get back in line, to see the people who pushed this program get punished, and for them to stop what they are doing…everyone needs to get together and stand up strong against this, and stop them.”

Rhonda Olson noted similar trends and said, “With everything going on today, this lawsuit is really great news. I am so thrilled to be a part of such an important effort to help our entire community realize justice. This abatement program has devastated our county.”

The Institute for Justice is encouraging all abatement victims and concerned community members to join them today via Zoom at 11am (click here).

And though they can’t give advice to people who aren’t their clients. They encourage anyone who feels they’ve been harmed in the ways we set out in our complaint to contact Attorney Jared McClain directly at [email protected]

Read the law suit here: Humboldt Abatements – Complaint

Special thanks to the UC Berkeley Cannabis Research institute for their data analysis expertise and ongoing support of this work.

If you value Nichole Norris’s investigative journalism please donate at her Gofundme.

In addition, please donate to Redheaded Blackbelt, because without Kym Kemp none of this would have happened, according to Nichole Norris…

If you have any questions or comments you can reach this reporter, Nichole Norris at [email protected]

Earlier:

Be the first to comment