ONE OF THE main arguments in favor of legalizing recreational marijuana was that consumers would have access to tested, regulated products, and know exactly what they are buying.

But a CommonWealth investigation reveals that the potency levels listed on websites and product labels at marijuana stores are regularly inflated, sometimes by as much as a third. The investigation also found that some products in Massachusetts cannabis stores tested positive for contaminants that would have kept them off the shelves if they were detected earlier because they were potentially unsafe for human consumption.

The findings suggest that marijuana consumers cannot rely with any confidence on product labels. Labs are performing tests using different technologies and methods, and growers are gravitating to labs that report the highest THC levels or pass the most samples for contaminants, even if their testing methods are not the most scientifically accurate. That, in turn, is creating incentives for labs to generate testing results with higher THC readings.

It’s all giving the behind-the-scenes world of the new legal cannabis industry a Wild West feel, without professional standards, regulations, or stringent oversight guiding the testing of marijuana. Meanwhile, the office in charge of policing the state’s four-year-old recreational marijuana sector doesn’t seem eager to address any oversight or regulatory shortcomings that may warrant attention. The state Cannabis Control Commission’s press staff referred a reporter to state rules governing lab testing, but declined repeated requests to make a commissioner or staff member available for a discussion of the matter.

Commissioner Kimberly Roy has previously called for the formation of an independent standards lab, which is a lab that can be used to set standards against which other labs can be measured. Speaking to CommonWealth briefly after a call on an unrelated matter, Roy said she is “very mindful of these concerns” about different testing methods. “Our independent testing laboratories, in the absence of a standards lab, must be good stewards and honest brokers for the cannabis industry in Massachusetts,” Roy said. “At the end of the day, consumers and patients need to know that their products are safe and properly tested.”

Some industry officials are seeking more regulation of the industry. Nick Masso, CEO of Marlborough-based Indo Labs, who reviewed the investigation results at CommonWealth’s request, said it is currently left to the labs to police themselves, and there are a lot of gray areas within the rules governing testing. “If this industry truly wants to become legitimate and destigmatized, and especially move toward a level of integrity, we need to make sure we’re holding the lab accountable for the data which they’re producing,” Masso said.

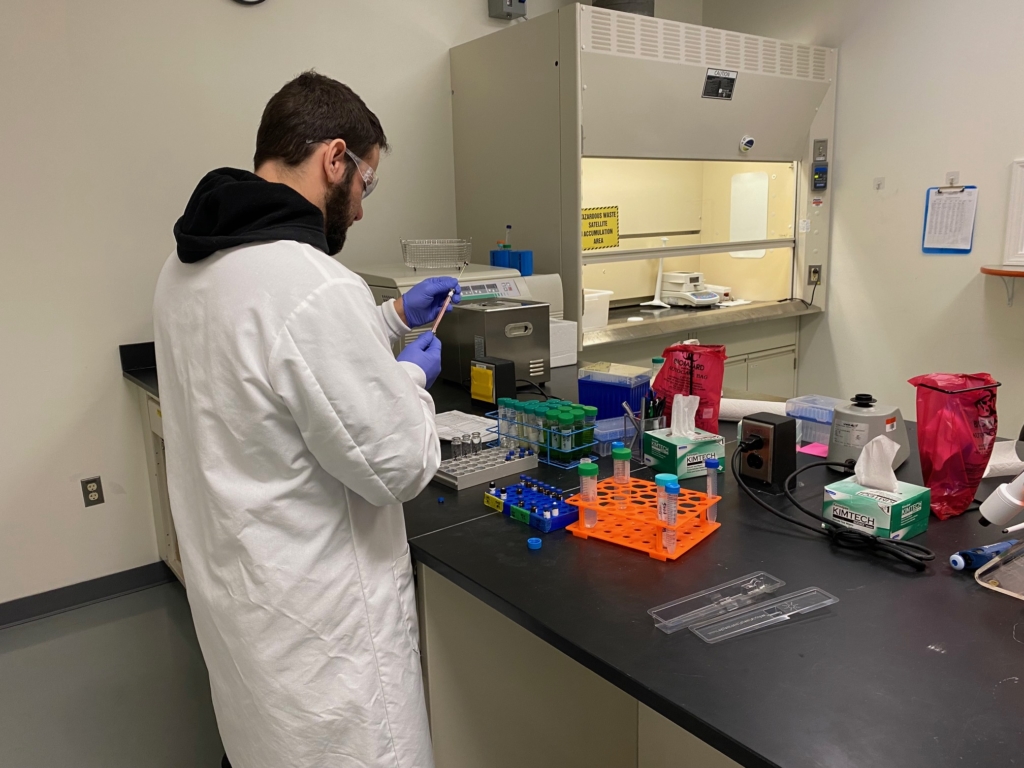

Cannabis is tested at Indo Laboratories in Marlborough on November 21, 2022. (Photo by Shira Schoenberg)

A SECRET SHOPPER CAMPAIGN

In November, when CommonWealth was conducting its investigation, Blackstone Valley Cannabis in Uxbridge was selling a strain of marijuana called Bubba Kush, which the Leafly cannabis marketing website described as a “skunky but fruity hybrid” with 32 percent THC, which is the compound that makes someone high. The label on the store’s Bubba Kush container said the flower was made up of 33.46 percent total cannabinoids and 32 percent THCa, which is the acid that breaks down to THC when burned. A product with 20 percent or more THC is considered high potency.

The Bubba Kush sold by Blackstone Valley was grown by Green Meadows Farm of Southbridge, which had it tested for THC and contaminants by a lab called CDX Analytics. A five-page document from CDX said the Bubba Kush flower was tested in September, yielding the THC percentages on the product label and certifying that the marijuana passed state-required tests for microbial contaminants, pesticides, and metals.

Yet when the Bubba Kush was tested at three other labs in November, at CommonWealth’s request, the amount of THCa detected ranged from 20.6 percent to 25 percent, about a third less than advertised. Total cannabanoids were between 22 percent and 26.3 percent, also about a third lower than advertised. The three labs cleared the Bubba Kush for contaminants.

Three other marijuana flower samples purchased at Blackstone Valley, Green N’Go in Uxbridge, and MedMen in Boston were also analyzed by the three labs – ProVerde in Milford, MCR Labs in Framingham, and AtoZ Laboratories in Hopkinton – and the THC potency in each case was lower than what was on the product label. There were differences among the three labs that conducted the follow-up testing, but they were relatively small.

Two of the marijuana samples failed tests for contaminants. A sample of Zebra Cake flower, made by Sanctuary Medicinals and bought at Green N’ Go, passed its microbial screening at MCR Labs in June 2022. MCR Labs passed the sample again in November. But both AtoZ Labs and Proverde failed the sample, identifying the presence of bile-tolerant gram-negative bacteria, a group of bacteria that can be found in the gut. AtoZ also identified a higher than allowed level of coliforms, bacteria that can cause E. coli.

A sample of Mile 62 Butterstuff, grown by MassGrow, packaged and branded by Revolutionary Clinics, and bought at MedMen, passed its yeast and mold test at Kaycha Labs in August 2022 but failed for yeast and mold at ProVerde Labs in November, which detected more than twice the legal limit.

Jeff Rawson, a former Harvard postdoctoral fellow in chemistry and the founder of the nonprofit Institute of Cannabis Science in Cambridge, conducted similar tests earlier this year that yielded very similar results. The results, published on Rawson’s website, found that for every one of the 15 samples he had tested, the average THC measured by the three labs in subsequent testing was lower than what was advertised on the label. Rawson also did microbial testing to identify contaminants for 10 of the samples, and two tested positive – one for mold and one for bacteria.

“People are being defrauded,” Rawson said, adding that it is “absolutely a safety issue.”

TESTING METHODS AND DIFFERENCES

There are legitimate reasons why test results might change over time. Margaret Teasdale, chief science officer at CDX Analytics in Salem, which did the initial testing of the Bubba Kush sample, said one explanation can be as simple as the fact that marijuana has a short shelf life. Teasdale said storage temperature, the storage container, and exposure to light can all affect potency. Teasdale said CDX did its own random testing of marijuana bought off the shelves and discovered that only the samples that were less than a month old had a potency concentration within 5 percent of what was listed on the label.

Investigations in other states have found problems with potency inflation, or labs fraudulently inflating levels of THC. While there is no evidence of outright fraud in Massachusetts, it is clear that murky guidelines and a lack of standards lead to labs performing tests and reporting results in different ways.

For example, CommonWealth purchased a sample of Motor Breath flower at Blackstone Valley Cannabis. It had been grown by Harbor House Collective in Chelsea and tested at Analytics Labs in Holyoke. Analytics measured the THCa content of the Motor Breath at 37.5 percent, while the other labs produced measurements ranging between 30.3 percent and 33.7 percent. Analytics Labs reported total active THC of 34.68 percent, while tests at the other labs ranged from 27.6 percent to 30.85 percent.

State guidelines say the potency of flower should be calculated based on the weight of the marijuana after it has been dried. But there is a disagreement among labs about what “dry” means. Cannabis flower that is sold has been dried, but it also retains some moisture.

Brenda Shalloo, chief scientific officer of Analytics Labs, said her company uses a mathematical formula to calculate the potency if all the moisture were removed. ProVerde, by contrast, tests the sample as is and reports that potency number, while MCR’s reports include two potency calculations, one with and one without moisture. Officials at those labs say consumers should know what they are getting, and including the mathematical calculation implies that the marijuana is more potent than it actually is.

Labs also measure THC differently. Analytics Labs includes d8-THC and THCV in its calculation of total THC, which are types of cannabinoids that have specific effects; ProVerde excludes those compounds. (With the samples CommonWealth had tested, that was not an issue, since those compounds were not detected.) The measure of total cannabinoids published on a label actually means the total cannabinoids each lab tests for. In the samples’ original certificates of analysis, MCR Labs listed 19 cannabinoids it tests for, Analytics Labs listed 13, X Analytics listed 12, and Kaycha Labs listed 11.

Brenda Shalloo, chief scientific officer at Analytics Labs in Holyoke, holds up marijuana samples on November 30, 2022. (Photo by Shira Schoenberg)

There are also very different methods that can be used to test cannabis. One stark example is in testing for contaminants. One technology that can be used to conduct microbial tests is a qPCR test, similar to the technology used to test for COVID-19. The qPCR test was banned in Nevada, Michigan, and Maine for use in measuring yeast and mold in cannabis, and in Nevada and Maine for measuring certain types of bacteria, because it was determined not to yield scientifically accurate results.

Officials at multiple Massachusetts labs, including Analytics Labs, told CommonWealth that they tried using PCR-based technology, but it failed to detect yeast and mold that was identified using a more traditional method called plating. Massachusetts, however, has not banned the use of qPCR tests, which are faster than traditional lab tests, and some labs use it.

AtoZ, for example, uses mainly qPCR tests for contaminants. For CommonWealth, AtoZ tested each sample using a qPCR test and confirmed it with a plating technique. One sample passed with plating and failed with qPCR; a second sample passed with qPCR and failed with plating.

Alejandro Gutierrez, a chemist at AtoZ Labs, said qPCR is a validated method, but he acknowledged that some contaminants may fall through the cracks, and every testing method has weaknesses. “You can have a validated method that’s worse at detecting everything than other validated methods,” Gutierrez said.

Another place where disparities can be introduced is in the standard scientists use to calibrate the machines used to determine THC potency. Standardization is a way to set a baseline for what a THC level of 10 percent or 100 percent looks like, so samples can be measured against that. There are national standards that tell health care professionals how to calibrate medical devices to ensure they give accurate readings. There are no national standards for measuring cannabis potency.

Meredith Gutierrez, a chemist at AtoZ Labs, said there might also be differences in sample homogenization, the extraction process, or instrument sensitivity. “Ideally, we’d like to get to a standardized method,” Gutierrez said. “I think that’s still a ways down the road.”

There is no federal guidance on cannabis testing, since marijuana remains federally illegally. So it is up to state regulatory bodies to write testing rules.

The Cannabis Control Commission requires testing labs to be accredited by a national lab accrediting organization. But the accreditation covers topics related to labs overall, not cannabis-specific issues like which testing methods are reliable or what standards to use to calibrate specific machines. Several industry insiders say the Cannabis Control Commission lacks the technical expertise to develop and enforce those types of standards.

“Without the proper regulatory guidance and oversight in place from these cannabis control commissions in various states, it’s very easy for people to open up a lab and get away with a lot of bad practices or lenient practices or altogether fraud because there’s no real oversight once they get their license,” said Masso, of Indo Labs.

Masso said the Cannabis Control Commission tells labs what to test for, but not how to do the tests. “Without having method standardization, if you send your product to three different labs, you’re going to get three different results,” Masso said.

Because cultivators can have their marijuana tested at any accredited lab, labs have a financial incentive to get results that will attract and retain clients.

“Some of them are trying to do what they know gets the business. They’re also getting pressure from the product manufacturers who want to see certain results,” Masso said. “And that’s without any proper oversight and without a standard for how these labs have to test.”

Even if all the labs are well-intentioned, the simple fact of variance in testing results is a problem, particularly for medical marijuana patients, Masso said. “If you went to a pharmacy, would you accept different concentrations of medication or an altogether different medicine?” he asked.

CommonWealth tried to find out if some labs pass far more samples than others by filing a public records request with the Cannabis Control Commission asking for each lab’s fail rate of tests for microbiological contaminants. Commission general counsel Christine Baily responded that the commission’s database cannot create a report with that information. “The Commission does not retain its own database of historical test results,” Baily wrote in her response.

Current laws also open the door for the potential manipulation of samples by cultivators.

Under state regulations, marijuana growers can choose which sample to submit as long as the sample is representative of an entire batch, and a batch is no more than 15 pounds. Industry observers say the fact that cultivators can choose the samples themselves opens the door to unscrupulous cultivators acting improperly by treating a sample differently from the rest of the batch – dusting it with kief, which is ground marijuana powder, to increase potency, or treating it with radiation or ozone to eliminate contaminants.

A cultivator can pick a sample from a less moldy part of a plant, or from the top of a plant where it receives the most sunlight and has higher cannabinoid content.

There is also natural variability within any plant. Erik Williams, chief operating officer of Canna Provisions, which does cannabis cultivation and retail, said he recently tested four samples from one harvest of flowers cloned from the same plant. Three came back with virtually identical THC levels, but one sample had a 6 percent difference. “The expression of a flower from top to bottom can be very different,” Williams said.

Cultivators have a strong financial incentive to get results that measure high THC levels, because that is what many consumers look for. Ed DeSousa, cofounder of North Reading cultivation company River Run Gardens, said stores will not buy wholesale from him if a batch measures less than 20 percent THC. “If it’s under 25 percent, they’ll want me to decrease the price per gram to a point that it’s break even or losing money,” DeSousa said.

Some lab officials and cultivators are actually seeking more state regulation of the industry as a way to level the playing field among companies. Ted Madru, principal at Analytics Labs in Holyoke, compared cannabis testing to two restaurants that make the same type of pasta dish but put different ingredients into the sauce. “We want more regulatory oversight so we’re all making recipes the same,” Madru said.

Lab officials worry that without more regulation and standardization, the labs that follow scientific best practices risk losing customers. Michael Kahn, founder and CEO of MCR Labs, said his lab has lost customers because it does not report the highest potency rates. “It’s known in the marketplace which lab will give you the higher potencies, and that’s where the market tends to start to go,” Kahn said.

Kahn said his lab also loses clients after failing them for contamination. A failure carries a huge financial cost because that batch cannot be sold. “Right now, whenever a client of ours starts to experience microbiological failure, we know we’re probably going to lose this client to some other lab really soon,” Kahn said.

Marijuana is tested at Analytics Labs in Holyoke on November 30, 2022. (Photo by Shira Schoenberg)

A LOSS FOR CONSUMERS

But it is consumers who have the most to lose if they do not know what they are ingesting. Several cannabis activists who use marijuana confirmed anecdotally what CommonWealth found: that labels are not always accurate.

“I’ve purchased low THC [marijuana] that had greater impact than higher ones,” said Carlha Toussaint, a Brockton resident who works in cannabis delivery and has advocated for improved disclosure. Looking at labels, Toussaint said, “I never felt like the potency mirrored or reflected what they’d say.”

Mike Crawford, who does a cannabis podcast and is a longtime medical marijuana patient, said he has long felt that product labels are inaccurate. “I don’t trust the testing,” Crawford said, citing the conflicts of interest in a market where marijuana growers can choose their own samples and shop around for the best lab results.

Janet Joy use marijuana and is a caregiver for her mother, a medical marijuana patient in Chicopee, and she also used to work in a cannabis dispensary. Joy said she personally will not rely heavily on what is on a product’s label, since she questions its reliability. But she also needs to rely on the label when shopping for her mother’s medicine to know what compounds are in the medication and at what potency, since her mother also takes traditional medications that can interact badly with certain components of marijuana.

“Especially for people that are using cannabis medicinally, mislabeling can be a huge factor and have health repercussions,” Joy said.

SHARE

The Best Legal Delta 9 Near You in Park Forest North

The Best Legal Delta 9 Near You in Park Forest North

Be the first to comment