Contents: Flower Power // Bud Shop // Skunk Works

Cannabis is on the march in Michigan, from a proliferation of multimillion-dollar, climate-controlled marijuana-growing facilities to dozens of sleek retail “dispensaries” for cannabis products, and from makeshift drying houses in old barns to new investments aimed at changing the economic course of entire towns.

In fact, the legal cannabis trade already has estimated revenue of close to $2 billion a year statewide in absolute terms and on a per capita basis, in the wake of Michiganders’ 2018 vote to legalize marijuana for recreational purposes beginning in late 2019, which elevated legal weed’s status from “medical” applications only.

Cannabis sales in the state are likely to reach around $3 billion before leveling off in the next few years, according to a study by Michigan State University in East Lansing. Meanwhile, Michigan ranks as one of the biggest legal cannabis markets in the nation, both in absolute terms and even more so on a per-capita basis.

“There’s been a lot of suppressed interest in this product,” says Ankur Rungta, co-founder and CEO of C3 Industries Inc., a multistate cannabis cultivator, processor, and retailer based in Ann Arbor. “We’ve not allowed this plant and all its derivatives to be properly studied and looked at from a medical and recreational standpoint. What we’re seeing is something that had widespread use in our society now being brought into the mainstream, and being funded more directly by capital markets, scaled up, and brought into the modern-day economy.”

Here’s where comprehending the fantastic growth of the cannabis industry in Michigan becomes a bit of a mind-bending experience. In many ways cannabis is developing conventionally, as other businesses have, with eager entrepreneurs rushing in, facilities under development, new government regulations, retail markets sprouting, and even entrenched competition complaining. And it’s being marketed much like tobacco was in decades past, with media-savvy messages meant to hook young users. Add to that the fact that although it’s still illegal federally, recreational marijuana use is legal in 18 states and counting.

And yet, at the base of it all, we’re talking about … pot. Grass. Mary Jane. Reefer. The stuff that young boomers toked for fun in college and then, for the most part, gave up as unnecessary, if not illegitimate, for the rest of their lives. Yes, the substance is less harmful to the lungs than cigarette tobacco, and it’s a depressant that acts a lot like alcohol in its effects, but it’s also a hallucinogenic and may well be a gateway to other drug use. Not to mention that it could be causing other problems, such as the likelihood that driving high has contributed to an 11-percent increase in U.S. road traffic deaths last year.

There’s a term people in the cannabis industry use for those who are interested in marijuana and its derivative products but are uncertain about whether and how to proceed: “canna-curious.” While true believers interpret this hesitancy as, “Is there really something in cannabis for me?” the fact is that many Michiganders are just asking, “What the hell is happening here?”

Part of the reason for the difficulty in contextualizing the boom in cannabis sales is that comparisons are elusive. The trend has a bit of the feel of the neck-snapping build-out of the internet in the late 1990s and the simultaneous boom in e-commerce, because that phenomenon also appeared relatively quickly and was similarly difficult for many people to get their head around.

Yet unlike uncanny phenomena that fizzle out, such as the dot-com boom then, or perhaps plant-based “meats” today, the groundswell in cannabis legalization and consumption has the feel of permanence. When the haze of the early days of this business clears, cannabis is likely to remain a medical, social, and even cultural institution. Driven largely by millennials and Generation Z, mainstream marijuana is another one of those huge generational transformations.

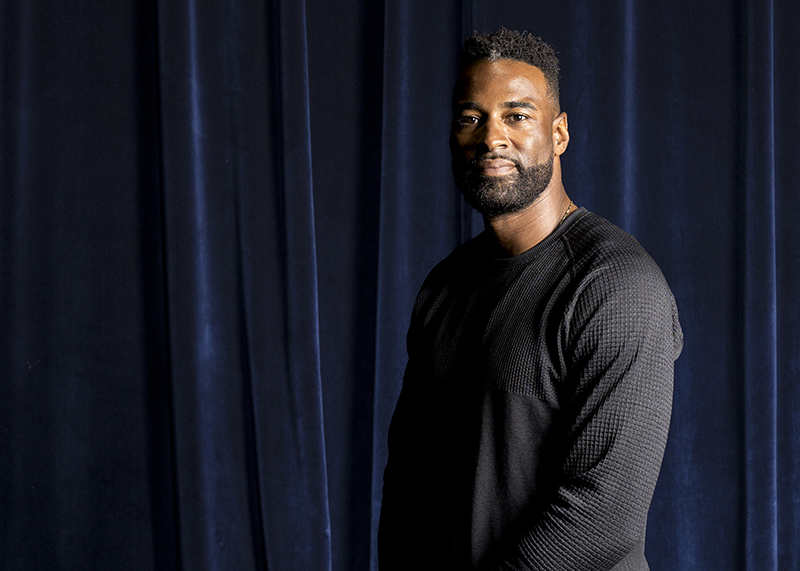

“Cannabis is emerging from something with a stigma to something that’s seen in a positive light,” says Rob Sims, a former guard for the Detroit Lions who co-founded a vertically integrated cannabis company, Primitiv, with Lions Hall of Fame receiver Calvin Johnson. The pair operates a 12,000-square-foot growing operation in Webberville and a dispensary in Niles.

“Ninety-year-old grandmothers have thanked me for something that helps them feel better, athletes are taking it for bumps and bruises, and (it’s being used for) everything in between, (by) the healthiest of people to those on their last legs. People are seeing the truth,” Sims says.

The two ex-footballers have ambitions to create more medical uses for cannabis and other natural substances such as psilocybin, the hallucinogenic chemical in “magic” mushrooms. They’ve created a collaboration with Harvard University to research how such substances can help people with chronic pain and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a progressive brain condition that’s thought to be caused by repeated blows to the head, such as those sustained by football players.

“Cannabis is one of those things that’s a natural substance, but where smoking (it) might not have been the best application,” Johnson said at a recent MLive cannabis conference at the Garden Theater in Detroit’s Midtown. “But we know a lot more now.”

Ben Wallace agrees. “I never really was a marijuana smoker,” the defensive menace, who was a star with the Detroit Pistons for nine NBA seasons and was the first undrafted player inducted into the NBA Hall of Fame, says. “But to see guys come out of the sport and have chronic pains, aching joints, and stuff like that made me interested, so I gave it a try. It did help me with my aches and pains, so I thought I’d take this opportunity to get behind it and sort of help drive medical marijuana.”

The new cannabis economy in Michigan isn’t just built around sports stars. It has several dimensions and multiple layers, attracting eager young entrepreneurs, rappers, buttoned-up attorneys, and sober owners of existing businesses.

Andrew Blake owns a thriving family entertainment business in Armada — a big farm that offers fall pumpkin hunts, fruit and vegetable-picking in the summer and autumn, a restaurant, and other attractions. He also owns Blake’s Hard Cider.

Recently, Blake struck a deal with Pleasantrees to open a beverage-processing facility at the site of the former Gibraltar Trade Center in Mount Clemens. The beverages will include cannabinol (CBD), the chemical in cannabis that’s reputed to have many therapeutic effects but isn’t a psychotropic like tetrahydrocannabinol (THC).

Randall Buchman is president and CEO of Pleasantrees, which has built an impressive 110,000-square-foot cannabis growing and processing facility in Harrison Township alongside I-94. “I started growing it in my parents’ basement, and here we are,” says Buchman, whose financial backers include Skypoint Ventures, a Flint-based venture capital firm. “I got into James Madison College at MSU but then decided I didn’t want to be president (of the United States). I sold weed in college, which paid most of my tuition.”

Now, Buchman is doing cannabis deals with financial stakes that he never imagined for what once was a pastime. “This business is so nascent that in every single situation, you’re playing monopoly with real estate,” he says. “The deal structure and the flow is endless. It’s all unique.”

Howard Luckoff might be the ultimate example of bringing establishment legitimacy to the newly clean cannabis business. A boyhood friend of Dan Gilbert and more recently the general counsel for Gilbert’s Rock Ventures, as well as a former board member of Shinola, Luckoff was still practicing real estate law for Honigman, a large law firm in Detroit, when one of his now-partners was investing passively in the cannabis space.

“It was a new frontier, like at the time of the end of Prohibition, and I wanted to be part of a brand-new industry,” says Luckoff, CEO of New Standard in Bloomfield Hills. “I’m a silk-stocking lawyer, still in other businesses. My kids ask what they should say that I do. I say, ‘I’m in the retail business.’ It just happens to be for an agricultural product that we create. And it happens to be cannabis.”

Whatever its status now, the journey to legitimacy for cannabis has been a long one. The federal government first regulated marijuana in 1937, when Congress passed the Marijuana Tax Act, which used taxation and regulation to essentially outlaw the possession or sale of marijuana. The Boggs Act of 1953 provided criminal sanctions of stiff mandatory sentences for offenses involving a variety of drugs, including marijuana.

The 1960s, with the rise of the youth counterculture and illicit drug use, of course changed all of that. It was partly his disdain for that generation which reportedly led President Nixon to push his War on Drugs and to include marijuana — along with heroin and LSD — in “Schedule 1,” the most-restricted category in the Controlled Substances Act that Congress passed in 1970.

Yet while many adults who came of age in that era left cannabis behind, others kept using it recreationally and, as they aged, they found it was effective to treat aches and pains. Groups such as NORML (National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws) and publications such as High Times helped create a popular basis for legalized marijuana.

Their opening came with the decriminalization of medical marijuana in Oregon, Alaska, and Maine in the 1970s. The move was depicted as an aid for people suffering from ailments ranging from social anxiety to glaucoma. In 1996, California voters became the first to legalize marijuana for medical purposes at the state level.

While 18 states, Guam, and Washington, D.C., now have approved recreational cannabis, states such as Florida still forbid it. The plant in all forms is still illegal in Idaho, Kansas, South Dakota, and Wyoming. Meanwhile, continued federal illegality of cannabis means that multistate operators such as C3 must, at this point, grow, process, and sell all their marijuana in each state that’s a market for them. They can’t legally cross state lines with cannabis.

In Michigan, there are 540 medical dispensaries catering to 230,500 patients, and 478 recreational dispensaries. Recreational cannabis customers pay a 10-percent excise tax on top of the state sales tax, while medically designated customers don’t pay the excise tax. Yet the demise of Michigan’s 12-year-old medical-cannabis sector is ongoing, as recreational use continues to expand vigorously. Recreational sales surpassed medical sales in mid-2020, and the industry forecasts that medical receipts will be about $324 million this year.

The cannabis flower constitutes about 55 percent of cannabis products sold in Michigan, the state says, while non-flower products such as edibles and vapes comprise the rest of the market. The most popular products include CBD-infused edibles, vape cartridges, body oil, and topicals such as lotions, bath bombs, and tincture, an extract.

Michigan dispensaries set a record for cannabis sales this year on April 20, an unofficial annual holiday for marijuana smokers with its origins among Grateful Dead fans of the 1980s. The state’s stores sold 4,912 pounds of cannabis on April 20, more than double the 1,912 pounds sold on that day in 2021, and a level more than 10 times higher than the 430 pounds sold in 2020.

Even legal dispensing of marijuana is completely a cash business, because most banks and credit-card companies won’t process purchases of cannabis products. That means dispensaries often are targeted by thieves; in Seattle, for instance, a recent surge in robberies at licensed cannabis shops is helping fuel a renewed push for federal banking reforms that would make the stores a less appealing target.

In Michigan, the latest wave of cannabis facilities are “consumption lounges” — which, in essence, provide legitimate substitutes for college dorm rooms or a hiding spot in the woods. Hot Box Social, on John R Road in Hazel Park, opened in April and started hosting private events and ticketed experiences. Consumption lounges can’t sell weed or edibles, and Hot Box prohibits customers from bringing their own stashes. What customers can do is order from a menu of products made by local participating dispensaries like New Standard, and what they buy is quickly delivered to a counter at Hot Box.

The million-dollar building features 3,000 square feet of space and sliding-glass garage doors so the lounge can be cleared of smoke within 30 seconds. Out back, a 5,000-square-foot patio is expected to open this summer.

The million-dollar building features 3,000 square feet of space and sliding-glass garage doors so the lounge can be cleared of smoke within 30 seconds. Out back, a 5,000-square-foot patio is expected to open this summer.

Hot Box is just the latest cannabis facility in Hazel Park, which has become an interesting microcosm of the expanding industry in Michigan. It’s fitting: 75 percent of Hazel Park residents voted to legalize marijuana, and the city council recently approved the decriminalization of entheogenic plants, including magic mushrooms and peyote.

Hugging I-696 on the north, at least a half-dozen dispensaries and other facilities dot a square mile or so in the old industrial city, including several on John R and more to the south on Nine Mile Road. In addition to Luckoff’s New Standard shop, Trucenta, a Troy-based company that owns Hot Box Social, also owns the Breeze dispensary on John R. These places mix indiscriminately with other retail outlets on John R such as GNE Paint Centers and Sullivan’s Continental Bike Shop, and with local institutions such as St. Mary Magdalen Church.

Changes also abound at the state level. What was the Michigan Marijuana Regulatory Agency — the body overseeing the industry — recently was renamed the Cannabis Regulatory Agency under an executive order by Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, who gave the body authority to handle hemp products. All told, the cannabis excise tax generated more than $42 million last year, which is being doled out to the 163 Michigan communities that welcomed marijuana operations.

Municipalities are generally free to spend the cannabis revenue as they choose. Bangor Township near Bay City, for example, with 12 recreational marijuana shops last year, received $677,000 — a 19 percent boost to its 2020 budget. The township plans to use the funds to offset the costs of road repairs, a new firetruck, and police expenses.

Municipalities are generally free to spend the cannabis revenue as they choose. Bangor Township near Bay City, for example, with 12 recreational marijuana shops last year, received $677,000 — a 19 percent boost to its 2020 budget. The township plans to use the funds to offset the costs of road repairs, a new firetruck, and police expenses.

Meanwhile, Emmett Township, near Battle Creek in Calhoun County, with 11 dispensaries, was planning to spend its $667,000 windfall on ever-increasing public-safety costs and to restore services that have slowly evaporated over time, according to MLive.

In another layer of regulation, there continue to be tussles over how marijuana facilities will be managed in Detroit. The Detroit City Council recently approved a revised ordinance for awarding business licenses, after a longstanding disagreement among leaders and residents over how many cannabis sales opportunities should be specifically granted to longtime Detroiters. A federal judge halted the city’s initial ordinance last year after ruling the measure approved in 2020 was “likely unconstitutional” for providing too much preference to longtime residents.

A couple hundred miles to the northwest, rural Evart (south of Cadillac) is counting heavily on cannabis. The former logging community is one of the poorest municipalities in Michigan; its downtown is in decay and amenities are in short supply. But in 2020, Lume Cannabis got the go-ahead for legalized marijuana sales and opened a 50,000-square-foot growing facility in a newly established industrial park.

Founded by Bob Barnes Jr., the retired CEO and co-owner of iconic Michigan retailer Belle Tire, Lume was able to attract other investors who collectively have poured $65 million into what is now a 125,000-square-foot operation. Lume plans to double its presence in Evart with a carbon-copy facility just as big.

Indeed, cannabis is flowering all over Michigan. “Oregon is the most extreme and the most open and the most competitive state in the cannabis business, but Michigan is quickly approaching Oregon as one of the most open markets,” says Rungta, whose C3 Industries has nine stores in Michigan, with another five set to open soon. It also does business in Massachusetts, and is knocking on the door in Missouri, where voters are expected to approve adult recreational use of cannabis later this year. “It’s one of the largest markets in the country, from a revenue standpoint — larger than Massachusetts.”

Indeed, cannabis is flowering all over Michigan. “Oregon is the most extreme and the most open and the most competitive state in the cannabis business, but Michigan is quickly approaching Oregon as one of the most open markets,” says Rungta, whose C3 Industries has nine stores in Michigan, with another five set to open soon. It also does business in Massachusetts, and is knocking on the door in Missouri, where voters are expected to approve adult recreational use of cannabis later this year. “It’s one of the largest markets in the country, from a revenue standpoint — larger than Massachusetts.”

Why is Michigan such a great cannabis state? One reason is that it’s among the most populous to approve recreational use so far. There’s also the strong influence of the decades-old cannabis culture of Ann Arbor, where Rungta graduated from the University of Michigan Law School in 2008.

In a state once known for having a podiatrist on every corner to treat assembly line injuries, there’s also something to the need for the palliative effects of CBD and THC for an aging population. While Generation Z comprises the largest customer base at dispensaries in Michigan and nationwide, millennials aren’t far behind, and Generation X and boomers are numerous. The older the customer, the more they generally favor edibles, beverages, and tinctures over buying marijuana flower, retailers say.

Also, Michigan has developed a reputation for “really trying to tighten the parameters the right way, to make sure real business owners are coming into the space” and helping to flush out “bad actors in the gray market,” says Samir Pimputkar, co-founder of Cloud Cannabis in Troy, which has eight dispensaries in Michigan.

But there are stresses on Michigan cannabis growers, even as sales boom. Retail prices declined last year, in part due to the growth in the number of dispensaries and a dip in recreational prices that were affected by less expensive medical marijuana, often bought in larger quantities and without the state’s 10 percent excise tax. An eighth of an ounce of flower early last year sold for about $45, but now it can be bought in many dispensaries for around $20 or less.

“This is one of the only businesses where the cost of production has gone up but prices have gone down. They’ve crashed,” says Buchman, of Pleasantrees. “There’s an extraordinary supply in Michigan.”

Rungta goes further. “There will be winners and losers. There will be a wave of market corrections. If you don’t differentiate yourself and have a value proposition, you’re not going to make it. The level of pain will increase.”

That’s why cannabis entrepreneurs are unhappy with the looming competition from hemp, which is federally legal and grown all over Michigan for industrial uses. The state’s hemp producers have proposed that they be allowed to convert hemp oil through a chemical process into products for the licensed markets now occupied only by cannabis growers and processors.

“If you allow that into the TCH market, a lot of folks who’ve spent a lot of money to get compliance with cannabis regulations will have to compete with those in a much less regulated environment,” Pimputkar says.

But most cannabis players still look forward to a rising tide of interest and mainstreaming that will keep lifting their industry. “We need to educate people that this isn’t an illicit drug anymore, and that the plant has great attributes that will help you,” Luckoff says. “It will just take time.”

Bud Shop

As the cannabis sector gets more crowded due to rising competition and more product offerings, the best dispensary operators are differentiating themselves with exceptional branding, service, and merchandising, as well as promotional pricing.

Take New Standard’s dispensary on John R Road in Hazel Park, for instance. The company’s CEO, Howard Luckoff, applies marketing and customer service practices borrowed from Shinola, where he once was a board member, as well as from Apple and Starbucks.

“Our team members are educators,” Luckoff says. “What do you want to get out of this experience, and what do you want to learn? It’s about making both the connoisseur and the novice comfortable in our stores. We even have a loyalty program.”

New Standard’s appeal starts just inside the front door, where the brightly lit waiting area sports white-brick walls and olive-green, Mid-century-style chairs. A mellow tune from Sir plays on the store’s sound system.

A list of weekly specials greets customers: “Kiva, $15/all edibles” and “Tree Town, 4 for $30.” Just inside the door to the retail area is an ATM, because the business is all-cash due to federal limits on bank and credit card transactions.

Signs warn: “No weapons” and “No phone calls beyond this point” — a measure to try to prevent underage buying. A receptionist cards and registers each visitor before allowing them entrance through the locked doors leading into the store.

The day’s first clients are a handful of men who appear to be retirees.

No one is allowed to touch the merchandise, just to point to it or request it, so everything is behind or under glass. The first display a customer encounters is a jewelry-store-style table with many varieties of raw marijuana. The price is listed as $35 for each eighth-ounce.

The cannabis flowers — resembling small, green-dyed cauliflowers — are shown off in 4-inch-square Lucite boxes with metal tethers attached, a la department-store valuables. “Fifty percent of our sales are flowers,” Luckoff says. “You don’t have to put marijuana in your food anymore. In fact, we have marijuana brownies right over here,” he says, pointing to a shelf.

To the uninitiated, the array of 275 different products is dizzying. There are dozens of brands and flavors of gummies. There are cannabis mints, CBD-infused almond bites and peppermint patties, chocolate bars, and Ripple Quick Sticks.

The most popular edible, Luckoff says, is Wana Gummies. “It’s a West Coast brand,” he notes, “but they’re all manufactured in Michigan,” as all cannabis products sold legally in the state must be.

Under glass in an adjacent room are tinctures, topicals, flower grinders, pipes, and many other types of paraphernalia. Rise tincture, Luckoff promises, is “three drops, and 10 minutes later you’ve got a buzz.”

Luckoff’s tightly managed facility includes a backup generator on the roof. “If the power goes out, we’re still in business,” he says. “One day’s worth of revenue makes up for the cost.”

Out back, a team of workers attends to the pickup and delivery side of the business, which usually includes 60 to 70 deliveries a day in New Standard’s dedicated fleet of four cars. Because he launched the operation during the pandemic, Luckoff bought a house behind the dispensary and knocked it down to make room for the customer delivery operation.

From a dozen to about 20 New Standard staffers tend the facility throughout the day, including cashiers, “budtenders,” and someone to monitor the screen feeds from dozens of security cameras. Even in the labor-starved local economy, Luckoff says, New Standard easily recruits and keeps workers. “There’s no problem getting team members in this space,” he says. “Everyone wants to work in the cannabis industry.”

— Dale Buss

Back to top

Skunk Works

In a state full of fascinating tech centers and industrial facilities, Pleasantrees’ marijuana-growing and processing operation in Harrison Township can place a claim on being one of the most interesting operations around.

The multi-phase facility is in an unremarkable structure about the size of a Walmart, but Pleasantrees’ nondescript exterior belies the highly calibrated agricultural engineering wizardry on the inside. Pleasantrees complex of facilities here cost about $25 million to build, which is important because it’s harboring and monetizing tens of millions of dollars of marijuana every year.

“I talked to the best engineers about systems that weren’t used for growing cannabis and told them I needed them to apply this to cannabis,” says Randall Buchman, president and CEO of Pleasantrees. “A lot of this technology is similar to what you need for indoor tomato farming.”

But growing, harvesting, and processing cannabis to granular expectations is much more demanding than growing choice vegetables — which was apparent on a recent tour through the facility. “Companies are destined for failure if they don’t know what data to collect,” Buchman says. “It doesn’t cost me money to get better at what I’m doing, but it makes me more money.”

White lab coats are mandatory for visitors, and everyone who enters the operative part of the facility must go through an airlock that takes a couple of minutes to vacuum away all the hairs, crumbs, and other personal detritus that have settled on each individual.

The operation is divided into several huge rooms and some smaller ones, all fed by networks of pipes and conduits. The huge rooms each house dozens to hundreds of marijuana plants of different varieties, with growing conditions in each — light, temperature, airflow, moisture — kept optimal and delivered precisely, mimicking changes that would occur outside throughout the day and the growing season.

“Crop steering is so important,” Buchman says about how Pleasantrees uses data to optimize crops. “Just a 10 percent difference in yields means millions of dollars” in unrealized revenues, “even in less than a year.”

Racks of marijuana flowers, inventories of hundreds of thousands of dollars at a time, hang in drying rooms where they spend about 10 days. Once they’re dried, the flowers move into a living-room-size space occupied by about 20 people whose sole task is to use tiny scissors to trim the flowers into the usable and saleable portions. The strains have names like Acai Mint, and Apples and Bananas. “The worth of the flowers depends on the strain, its quality, and potency,” Buchman says.

A $5.5-million air-conditioning system out back is required to keep humidity and temperatures in line. “It allows me to hold tolerances tight,” Buchman says. “No one wants to spend that kind of money, but the ability to hone those conditions pays for itself many times over.”

The system also cleanses odors from the processing operation before emitting air from the facility to the outside, saving lots of complaints from the neighbors. Yet most everyone knows what Pleasantrees does: State regulators require the facility to mix its marijuana waste with cardboard, 50/50, because some desperate users otherwise would try to smoke the plant’s trash.

All the hardware, software, personnel, and inventory on hand underscore the tremendous seriousness of the Pleasantrees enterprise. Yet cannabis entrepreneurs like Buchman maintain a bit of an edge reminiscent of the decades the industry spent only in the underground.

For example, in Pleasantrees’ security room is a huge painting of one of the most famous photographs of Elon Musk: He’s smoking a joint on a Joe Rogan podcast in 2018. It’s a reminder that while the operation has a duty to maintain safety, there’s a fun side to the business, as well.

— Dale Buss

Back to top

Be the first to comment